Introduction

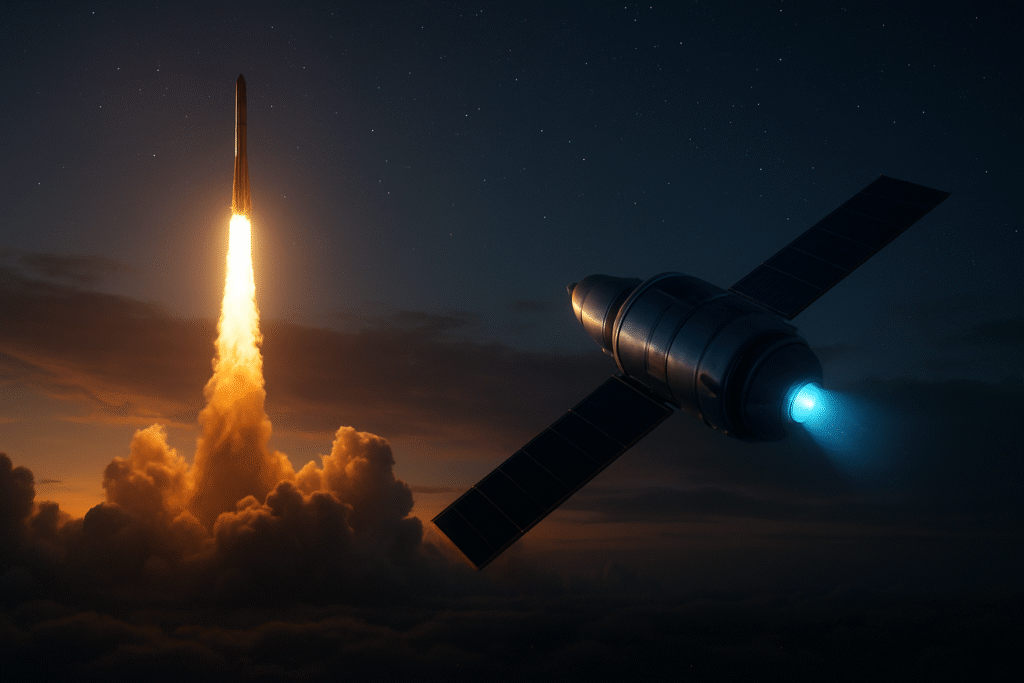

Watch a rocket launch—the ground shakes, a pillar of fire erupts, and a brilliant light carries a machine the size of a building gracefully into the sky. It’s a raw display of power. Now, picture a silent, unmanned probe, years into its journey, slowly and steadily adjusting its course in the void between planets. No fire, no roar.

What do these two scenes have in common? They both rely on the fundamental principles of rocket propulsion. But the engines they use are as different as a dragster and a Prius.

Why does this difference matter? Because in the high-stakes world of rocketry, you can’t just pick an engine at random. The choice of propulsion system dictates everything: whether you can escape Earth’s gravity, how much scientific equipment you can carry, and how quickly you can reach your destination.

This isn’t just technical jargon; it’s the story of how we get from here to there in space. So, let’s unravel the complex world of rocket science and break down the classification of rocket propulsion into a clear, understandable guide.

The Foundation: How Do We Even Classify Rockets?

Before we dive into the types, let’s establish the “why.” We classify rocket propulsion to make sense of the engineering trade-offs. The right engine for the job depends on the mission. Launching a satellite? You need brute force. Maneuvering that satellite in orbit? You need precision. Traveling to Mars? You need incredible efficiency.

The most common way to start is by looking at the physical state of the propellant—the stuff that gets thrown out the back to create thrust. It’s the most visible and fundamental differentiator.

The Primary Classification: Solid, Liquid, or Hybrid?

This is the classic divide, the one you’ll see in any rocket launch broadcast. It all comes down to how the fuel and oxidizer (the chemical that makes the fuel burn) are stored and mixed.

Solid Propellant Rockets: The Simple Firecrackers

Imagine a massive, industrial-grade firework. That’s essentially a solid rocket booster.

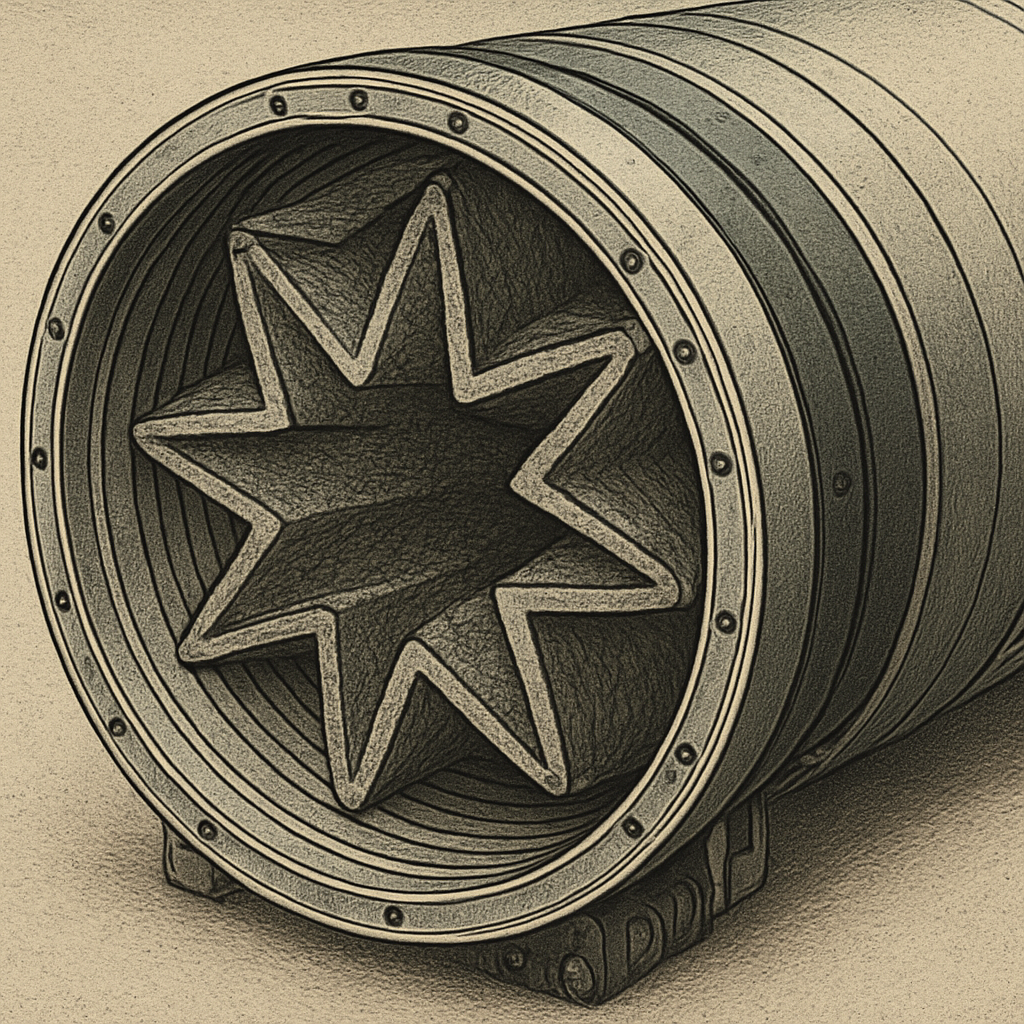

- How They Work: The fuel and oxidizer are pre-mixed into a solid, rubber-like material called a grain, which is packed inside the rocket’s casing. This grain has a specific star-shaped hole running through the center. When ignited, it burns from the inside out, and the shape of the hole ensures a consistent burn rate. Once you light it, there’s no stopping it until the fuel is gone.

- The Pros:

- Simplicity & Reliability: Very few moving parts. This makes them incredibly dependable.

- High Thrust: They produce a tremendous amount of push (thrust) right from the start, perfect for getting heavy rockets off the launchpad.

- Shelf-Stable: They can be manufactured and stored for long periods, ready for use.

- The Cons:

- No Off Switch: You can’t shut them down or throttle them. It’s “light the fuse and run.”

- Lower Efficiency: They are generally less efficient than their liquid counterparts, meaning you get less “push for your pound” of fuel (a property known as Specific Impulse or Isp).

- Where You’ve Seen Them: The most famous examples are the two giant white Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) on the Space Shuttle. They provided 71% of the thrust for the first two minutes of launch. Many missiles also use solid propulsion for their simplicity and instant readiness.

Liquid Propellant Rockets: The Controllable Powerhouses

If a solid rocket is a firecracker, a liquid rocket is a high-performance, finely-tuned car engine. This is the technology that took us to the Moon.

- How They Work: Here, the fuel (like refined kerosene or liquid hydrogen) and the oxidizer (usually liquid oxygen, or “LOX”) are stored in separate, super-cooled tanks. A complex network of pipes, valves, and incredibly powerful turbo-pumps feeds these liquids into a combustion chamber, where they ignite, creating a continuous, controlled explosion.

- The Pros:

- Total Control: The engine can be throttled up or down, shut off, and—crucially—restarted. This is vital for orbital maneuvers and precise landings.

- High Efficiency: Liquid engines are typically more efficient than solid ones, offering more bang for the buck (or more thrust for the kilogram).

- Power: They can generate an immense amount of power, making them the go-to for core stages of launch vehicles.

- The Cons:

- Complexity: They are engineering nightmares in the best way possible. The number of moving parts—especially the turbo-pumps spinning at tens of thousands of RPMs—means more potential points of failure.

- Cryogenic Challenges: Storing fuels like liquid hydrogen at -423°F (-253°C) is a huge technical hurdle.

- Where You’ve Seen Them: Nearly every modern rocket uses liquid engines. The SpaceX Merlin engines on the Falcon 9, the RS-25 engines on the Space Shuttle’s orange tank, and the legendary F-1 engines of the Saturn V are all iconic examples of liquid propulsion.

Hybrid Propellant Rockets: The Best of Both Worlds?

What if you could mix and match? Hybrid rockets attempt to do just that.

- How They Work: A hybrid rocket typically uses a solid fuel grain (often a plastic like HTPB) and a liquid or gaseous oxidizer (like nitrous oxide). The oxidizer is injected into the solid fuel, where it combusts.

- The Pros:

- Safer: The fuel and oxidizer are naturally separated, reducing the risk of accidental explosion.

- Controllable: Like liquid engines, they can be throttled and shut down by controlling the flow of the liquid oxidizer.

- Simpler than Liquids: They avoid the complex dual-turbo-pump systems of large liquid engines.

- The Cons:

- The Middle Ground: They can inherit some disadvantages of both, like the combustion inefficiency of solids and the added complexity of liquid feed systems.

- Less Common: The technology is not as mature, making it a less common choice for major launch vehicles.

- Where You’ve Seen Them: Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipOne and SpaceShipTwo use a hybrid rocket motor for their suborbital hops, burning a solid rubber fuel with liquid nitrous oxide.

Quick Comparison Table

| Feature | Solid Rocket | Liquid Rocket | Hybrid Rocket |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplicity | High | Low | Medium |

| Throttling | No | Yes | Yes |

| Restart Capability | No | Yes | Yes |

| Efficiency (Isp) | Low | High | Medium |

| Relative Cost | Low (per unit) | High | Medium |

The Big Picture: Classification by Energy Source

While the solid/liquid/hybrid classification is essential, it only tells part of the story. They all belong to a larger family: chemical propulsion. To get the full picture, we need to zoom out and see what fundamental energy source the rocket uses.

Chemical Propulsion: The Brute Force Family

This is the family we’ve been discussing. All chemical rockets work on the same principle: a highly exothermic (heat-releasing) chemical reaction between a fuel and an oxidizer creates hot, high-pressure gas that expands rapidly out of a nozzle, producing thrust.

- Principle: Newton’s Third Law in its purest form: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

- Best For: Anything that requires high power, especially fighting Earth’s gravity to achieve orbit. This is the only type of propulsion currently capable of launching from Earth’s surface.

Electric Propulsion: The Efficient Tortoise

If chemical rockets are sprinters, electric propulsion systems are ultra-marathon runners. They trade raw power for incredible, almost unbelievable, efficiency.

- How They Work: Instead of burning fuel, these systems use electrical energy (typically from solar panels) to accelerate charged particles (ions) of a propellant like Xenon gas to extremely high velocities. There are two main types:

- Ion Thrusters: Use electric grids to accelerate ions.

- Hall-Effect Thrusters: Use a magnetic field to trap electrons, which then ionize and accelerate the propellant.

- The Pros:

- Extreme Efficiency: They can have an efficiency (Specific Impulse) 5-10 times greater than the best chemical rockets. This means they use a tiny fraction of the propellant mass for the same mission.

- Longevity: They can run continuously for thousands of hours.

- The Cons:

- Extremely Low Thrust: The thrust of a typical ion engine is about the same as the weight of a single sheet of paper in your hand. It’s utterly useless for fighting gravity but perfect for the frictionless environment of space.

- Power Hungry: They require a lot of electrical power, limiting their thrust potential.

- Where You’ve Seen Them: NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, which orbited the protoplanets Vesta and Ceres, used ion thrusters. The Psyche mission, en route to a metal asteroid, uses them too. Perhaps the most widespread use today is on SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, which use Hall-effect thrusters for orbit raising and station-keeping.

Thermal Propulsion: The Next Frontier?

This category uses an external heat source to energize a propellant, which then expands and is expelled.

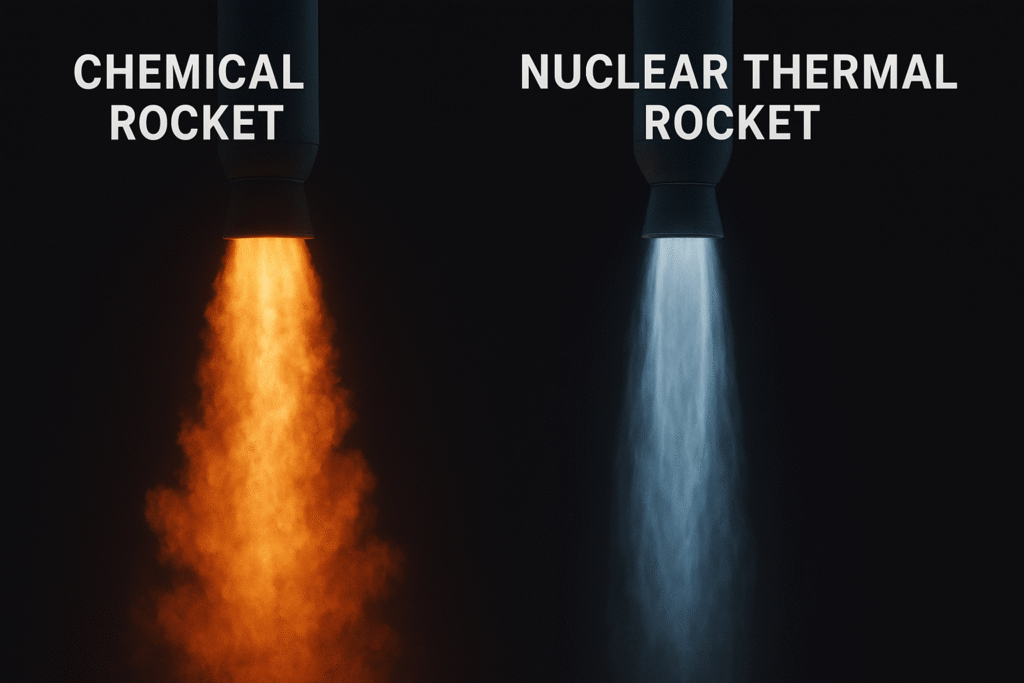

- Nuclear Thermal Rockets (NTR): This is the poster child for this category. A nuclear fission reactor heats a lightweight propellant like liquid hydrogen to extreme temperatures. The hot gas then rushes out the nozzle. Because it avoids the weight of the oxidizer and can heat the propellant to much higher temperatures than chemical combustion, it’s far more efficient.

- Pros: About twice the efficiency of chemical rockets, with enough thrust for practical interplanetary travel.

- Cons: The “N-word” – nuclear. This brings significant safety, political, and engineering challenges.

- Status: Heavily researched during the Cold War (Project NERVA) and now seeing a modern revival with programs like NASA’s DRACO, which aims to demonstrate a nuclear thermal rocket in space.

- Solar Thermal Rockets: These use giant mirrors to concentrate sunlight and heat a propellant. They are simpler than nuclear options but are limited by the available sunlight and the size of the mirrors required.

Other Important Ways to Slice the Pie

To be truly thorough, engineers classify rockets in a few other key ways:

- By Number of Stages: The “staging” concept is a workaround for the tyranny of the rocket equation. A single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) rocket is a dream for its simplicity, but no one has built a practical one yet. Multi-stage rockets (like the Falcon 9, Saturn V, or Soyuz) shed empty fuel tanks and engines as they ascend, making the remaining vehicle lighter and more efficient. The lower stage is all about power, while the upper stage is about precision.

- By Mission Type: The engine on a massive launch vehicle is designed for raw power in a thick atmosphere. A smaller orbital maneuvering engine is designed for fine-tuning a satellite’s orbit. Even smaller reaction control thrusters (like tiny puffs of gas) are used for attitude control—pointing the spacecraft in the right direction.

- By Oxidizer Source: This creates a fascinating branch of propulsion. Air-breathing engines, like scramjets, scoop oxygen from the atmosphere during flight, making them incredibly efficient for high-speed atmospheric travel. However, all rockets that operate in space must carry their own oxidizer, as there’s no air to breathe.

Conclusion: The Future is a Mix of Fire and Finesse

So, where does this leave us? The classification of rocket propulsion isn’t about finding a “winner.” It’s about understanding a toolbox.

For the foreseeable future, leaving Earth will remain the domain of powerful, thunderous chemical rockets—likely a combination of solid boosters for initial punch and sophisticated liquid engines for control and efficiency.

But once in the vacuum of space, the game changes. The future of interplanetary travel likely belongs to high-efficiency systems. Advanced electric propulsion will continue to push the boundaries of efficiency for cargo and robotic probes. And the long-dreamed-of nuclear thermal rocket may finally become a reality, acting as a fast interplanetary shuttle, cutting the travel time to Mars from months to weeks.

We are moving towards an ecosystem where different propulsion technologies are used in sequence, each playing to its strengths. The fiery chemical ascent, the gentle but persistent push of an ion drive through the void, and the powerful thermal nuclear burn for a planetary injection—this is the symphony of technologies that will take humanity to the stars.

What type of propulsion system fascinates you the most? Do you think nuclear rockets are the key to becoming an interplanetary species? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What is the most common type of rocket engine?

A: For getting into orbit, liquid-propellant engines are the most common for a rocket’s core stages due to their controllability and efficiency. However, solid rocket boosters are extremely common as supplemental thrusters strapped to the side of launch vehicles.

Q: What is the difference between thrust and efficiency (Isp) in rockets?

A: This is a crucial distinction! Thrust is the raw force—it’s the “brute strength” that fights gravity. Efficiency, measured as Specific Impulse (Isp), is like “fuel mileage.” A high-thrust engine (like a solid booster) might gulps fuel to create a huge push, while a high-efficiency engine (like an ion thruster) uses a tiny amount of fuel to create a tiny but sustained push. You need high thrust to leave Earth, but high efficiency to travel far in space.

Q: Why can’t we use electric propulsion to leave Earth?

A: Electric thrusters produce far too little thrust to overcome Earth’s powerful gravity. The weight of the rocket would instantly crush the tiny acceleration. It would be like trying to lift a car by blowing on it through a straw. They are exclusively for use in the weightless, frictionless environment of space.

Q: What fuel do most modern rockets use?

A: There are a few common pairs:

- Kerosene/Liquid Oxygen (RP-1/LOX): Used in SpaceX’s Falcon 9 (Merlin engines) and the Saturn V’s first stage. It’s a great balance of power and density.

- Liquid Hydrogen/Liquid Oxygen (LH2/LOX): Used in the Space Shuttle’s main engines and the core stage of NASA’s SLS. It’s very efficient but less dense and harder to store.

- Methane/Liquid Oxygen: The new contender, used in SpaceX’s Raptor engine (Starship) and Blue Origin’s BE-4. It offers a good compromise between performance, reusability, and the potential for being produced on Mars.

This response is AI-generated, for reference only.