Look up at the night sky. What do you see? Pinpricks of light, the glow of a nearby planet, the hazy band of our Milky Way. It’s beautiful, awe-inspiring, and… profoundly misleading.

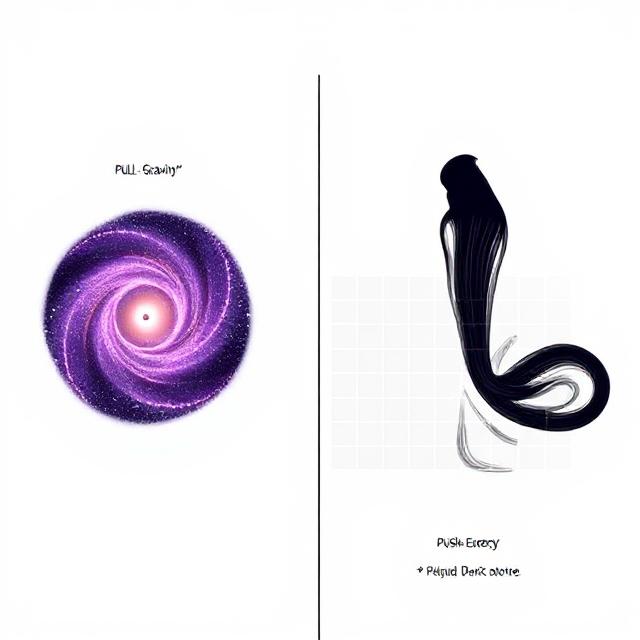

What we see with our eyes, and even with our most powerful telescopes, is less than 5% of the actual universe. The rest? A cosmic cocktail of mysteries: about 27% is Dark Matter, and 68% is an even more baffling force called Dark Energy. We are living in a universe where the vast majority of the stuff that governs its structure and fate is completely invisible to us.

It’s the ultimate cosmic detective story. And the key to solving it doesn’t just lie in looking at the stars of today, but in listening to the faintest echoes from the dawn of time—the early universe signals that carry the fingerprint of this invisible reality.

This is the story of that search. It’s a journey to understand the dark foundation of our cosmos by tuning into the universe’s oldest memories.

The Cosmic Crime Scene: What is Dark Matter, Anyway?

Let’s start with the culprit: Dark Matter.

We can’t see it. We can’t touch it. It doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect any light, hence the name “dark.” So how do we even know it’s there?

Imagine a merry-go-round spinning at a playground. The children sitting on it are held in place by the centrifugal force. Now, imagine if the merry-go-round was spinning so fast that the children were being flung off, but when you looked, you saw that most of the seats were empty. You’d know something was wrong. There must be some invisible, massive children holding on for dear life, providing the gravity to keep the whole thing from flying apart.

This is precisely what astronomer Vera Rubin observed in the 1970s with galaxies. She found that stars at the outer edges of spiral galaxies were orbiting just as fast as stars near the center. According to Newton’s and Kepler’s laws of gravity, these outer stars should be moving much more slowly, like the outer planets in our solar system. The only logical explanation? There must be a huge amount of invisible matter—dark matter—spread throughout and beyond the visible galaxy, creating a massive “halo” of gravity that whips the outer stars around at unexpectedly high speeds.

This isn’t a small miscalculation. For the math to work, there must be about five times more dark matter than normal matter (the stuff that makes up you, me, planets, and stars). It is the cosmic scaffolding upon which galaxies are built.

The Ghost in the Cosmic Machine: Properties of the Unseen

So, what is this stuff? We don’t know for certain, but we’ve deduced its properties:

- It Has Mass and Gravity: This is its defining feature. It interacts gravitationally, which is how it shapes galaxies and galaxy clusters.

- It’s “Cold”: In cosmology, “Cold Dark Matter” means it moves relatively slowly compared to the speed of light. This slowness was crucial for it to clump together and form the gravitational seeds for galaxies.

- It Doesn’t Play Well With Others: It seems to be completely transparent to light and doesn’t interact with normal matter via the electromagnetic force. It doesn’t bump into atoms. A particle of dark matter could be passing through your body right now, and you’d have no way of knowing. Millions of them are likely streaming through you every second.

The leading theoretical candidate for dark matter is a class of particles called WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles). But despite decades of searching in ultra-sensitive, deep-underground detectors, we haven’t caught one directly. Yet.

The Echo of the Big Bang: A Primer on the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)

To understand how dark matter shaped the early universe, we need a time machine. Fortunately, the universe provides one: the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

Imagine the universe just after the Big Bang. It wasn’t filled with stars and galaxies, but with an incredibly hot, dense, opaque fog of plasma—a searing soup of particles and light. Light couldn’t travel freely; it was constantly bouncing off electrons.

Then, about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, something monumental happened. The universe had expanded and cooled enough for atoms to form. Neutral atoms are transparent to light, so suddenly, the light that had been trapped could finally travel unimpeded across the cosmos.

That first flash of liberated light is what we detect today as the CMB. It’s the oldest “picture” we have of the universe, a fossil from its infancy. But because the universe has been expanding for over 13 billion years, that once-energetic light has been stretched, or redshifted, all the way down to the microwave part of the spectrum. It’s now just a faint, cold glow, a mere 2.7 degrees above absolute zero, bathing the entire cosmos.

When we point our telescopes at this background, we don’t see a perfectly uniform glow. We see tiny, tiny fluctuations—ripples of slightly warmer and slightly cooler spots. These ripples are the most important early universe signals we can study. They are the imprint of the initial density variations—the slightly over-dense and under-dense regions—in the primordial plasma.

Think of these ripples as the seeds of all cosmic structure. The slightly denser patches had a little extra gravity, pulling in more matter, eventually collapsing to form the first stars, galaxies, and galaxy clusters. And the gravity that orchestrated this cosmic symphony? It was overwhelmingly the gravity of dark matter.

The Smoking Gun: How the CMB Reveals Dark Matter

So, how does this ancient light, the CMB, tell us about the invisible dark matter? The connection is brilliant and multifaceted.

1. The Composition of the Cosmos

By studying the precise patterns of the CMB’s ripples—their size, distribution, and polarization—cosmologists can run the “movie” of the universe backwards to its first frames. The physics of the primordial plasma is so well-understood that the CMB acts like a cosmic recipe book.

The results from missions like the Planck satellite are unequivocal: the observed pattern of fluctuations can only be explained if:

- Normal Matter (Baryons): Makes up about 5% of the universe’s mass-energy.

- Dark Matter: Makes up about 27%.

- Dark Energy: Makes up the remaining 68%.

If you tried to model the CMB without dark matter, the math simply wouldn’t work. The observed acoustic peaks in the CMB power spectrum are a direct reflection of the tug-of-war between gravity (pulling matter in) and radiation pressure (pushing it out) in the early universe. The characteristics of these peaks are a dead ringer for the presence of a dominant, “cold” form of matter that doesn’t interact with light.

2. Gravitational Lensing of the CMB

This is where it gets even more fascinating. As the CMB light travels for 13.8 billion years to reach us, its path is bent and warped by the gravitational pull of all the matter—both normal and dark—it passes along the way. This effect is called gravitational lensing.

By studying the subtle distortions in the pattern of the CMB, scientists can create a map of the distribution of all the matter in the universe between us and the CMB. It’s like looking at a flickering light at the end of a long, warped glass tunnel; the distortions in the image tell you about the shape of the glass. These maps provide direct, powerful evidence for vast, interconnected cosmic webs of dark matter, exactly where our models of structure formation predict they should be.

Beyond the CMB: Other Early Universe Signals

While the CMB is our premier window into the early universe, it’s not the only one. Other cosmic messengers provide complementary clues.

1. The Formation of the First Galaxies

Dark matter’s role was to act as a gravitational anchor. After the CMB was released, the universe entered the “Cosmic Dark Ages.” The dark matter halos that had formed were quietly gathering more and more gas. Eventually, within these halos, the gas became dense enough to collapse and ignite the first stars.

The timing and the nature of these first galaxies are a key test for our dark matter models. If dark matter were “warm” or “hot” (moving at higher speeds), it would have smoothed out small-scale structures, delaying the formation of the first galaxies. The fact that we see very early, well-formed galaxies, like those recently observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, strongly supports the “cold” dark matter model.

2. Primordial Gravitational Waves (A Speculative Hope)

This is the frontier. Theorists believe that in the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe underwent a period of exponential expansion called inflation. This event should have created ripples in the fabric of spacetime itself: primordial gravitational waves.

While not directly a signal of dark matter, detecting these waves would give us a glimpse into the universe at energy scales a trillion times higher than what the CMB can probe. It could reveal physics that unifies all forces and potentially shed light on the nature of the particles, including possible candidates for dark matter, that were created in that fiery beginning.

The search is on, primarily by looking for a specific pattern in the CMB’s polarization, known as “B-modes.” Finding them would be like discovering the holy grail of cosmology.

The Future of the Search: New Eyes on an Old Sky

The mystery is far from solved. The next generation of experiments is being built to listen to these early universe signals with unprecedented precision.

- CMB Experiments: Projects like the Simons Observatory and the upcoming CMB-S4 in Chile’s Atacama Desert will map the CMB’s temperature and polarization with such exquisite detail that they could potentially detect the signature of primordial gravitational waves and measure the mass of the neutrino—another elusive particle—by its subtle effect on cosmic structure.

- 21-cm Cosmology: A new field aims to detect radio waves emitted by neutral hydrogen in the early universe during the “Dark Ages.” Mapping this 21-cm signal would provide a 3D movie of how the first stars and galaxies lit up and ionized the cosmos, directly probing the influence of dark matter at that epoch.

- Direct Detection: Experiments like LUX-ZEPLIN and XENONnT continue their painstaking hunt deep underground, hoping to catch the rare, tell-tale collision between a WIMP and a normal atomic nucleus.

FAQ: Your Dark Matter Questions, Answered

1. If we can’t see dark matter, how do we know it’s really there?

We know it’s there through its gravitational effects, like a detective finding an invisible culprit by following their footprints. The most famous evidence is from galaxy rotation curves. Stars at the edges of galaxies orbit so fast that without the extra gravity from a massive, invisible “dark matter halo,” they would be flung off into space. We also see its gravitational fingerprint in the way it bends light from distant galaxies (gravitational lensing) and in the precise patterns of the ancient Cosmic Microwave Background.

2. What is the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) in simple terms?

The CMB is the “afterglow” of the Big Bang. Imagine the universe as a hot, foggy fireball. About 380,000 years later, it cooled enough to become transparent, releasing its first burst of light. That light has been traveling for 13.8 billion years and has stretched into a faint microwave glow that uniformly fills the entire sky. It’s the oldest “baby picture” of our universe, and its tiny temperature variations are the blueprints for all future cosmic structure.

3. Could dark matter be made of black holes?

This was a serious hypothesis, known as MACHOs (Massive Compact Halo Objects). However, observations have largely ruled this out. If dark matter were primordial black holes from the early universe, we would see their gravitational effects when they pass in front of stars (microlensing). We haven’t seen enough of these events to account for all the dark matter. The leading candidate remains a new, fundamental particle, like a WIMP.

4. Can we touch or feel dark matter?

Probably not, and you wouldn’t know if you did. The leading theory is that dark matter particles are “weakly interacting,” meaning they pass through normal matter almost completely unaffected. Billions of them are likely streaming through your body every second without a single collision. Building detectors to catch one of these incredibly rare interactions is the goal of direct detection experiments, which are housed deep underground to block out other particles.

5. What’s the difference between Dark Matter and Dark Energy?

This is a crucial distinction! Dark Matter is an invisible form of matter that acts through gravity to pull things together. It’s the cosmic glue that holds galaxies and clusters together. Dark Energy, on the other hand, is a mysterious property of space itself that causes the universe’s expansion to accelerate. It’s a repulsive force that pushes things apart. Think of Dark Matter as the builder of cosmic structures, and Dark Energy as the force trying to tear the cosmic canvas itself.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Symphony of the Cosmos

The story of dark matter and early universe signals is a testament to human curiosity and ingenuity. We are cosmic detectives, piecing together a puzzle where the main suspect leaves no visible trace. We know it by its shadow, by its gravitational handiwork.

By listening to the faint whispers from the beginning of time—the cosmic microwave background, the distribution of galaxies, the potential ripples in spacetime—we are slowly deciphering the identity of the invisible architect of our universe.

We are like people listening to a grand, cosmic symphony. We can hear the music—the planets, the stars, the galaxies—but we are only now developing the instruments to hear the deep, fundamental bass note, the rhythm set by dark matter at the very dawn of creation. The melody is beautiful, but the true masterpiece lies in understanding the underlying harmony that holds it all together. The search continues, and with it, our understanding of our own place in this vast, dark, and magnificent cosmos.