When we picture our solar system, our minds often conjure a tidy, classroom-style diagram: the Sun in the center, followed by a neat line of eight planets, maybe with a few rings and a comet photobombing the edge. It’s a simple, almost serene image.

But this image is a lie. A beautiful, oversimplified lie.

The reality is far more chaotic, dynamic, and breathtakingly crowded. The solar system isn’t a series of lonely orbs circling a star; it’s a bustling cosmic metropolis. The planets are the major downtown districts, but the real action, the history, and the countless stories are found in the suburbs and the hinterlands—in the vast, swirling sea of small bodies.

Welcome to the realm of asteroids, comets, and moons. These are the solar system’s unsung heroes, the leftover building blocks of planetary formation, and the key players in a gravitational dance that has shaped everything we know. They are time capsules, potential threats, and future resources, all rolled into one. Let’s embark on a journey to understand these fascinating objects and the forces that guide their eternal motion.

Part 1: The Asteroids – Rubble of a Failed Planet

Between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter lies a region that defied the expectations of early astronomers. Instead of finding a planet, they discovered a vast belt of rocky debris: the Asteroid Belt.

What Are They?

Asteroids are essentially rocky remnants left over from the early formation of our solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. Think of them as the construction rubble that never got incorporated into a planet. The prevailing theory is that Jupiter’s immense gravity stirred up this region so violently during the solar system’s youth that the material there could never coalesce into a full-sized planet.

They are not uniformly distributed; the average distance between two asteroids is about a million miles. If you stood on one, you’d likely not even see your nearest neighbor. Collisions do happen, but they are rare on a human timescale.

A Diverse Cast of Characters: Asteroid Classification

Not all asteroids are created equal. They are categorized into several groups based on their composition and location:

- C-type (Carbonaceous): The most common type, making up about 75% of known asteroids. They are incredibly dark, ancient, and rich in carbon and water-bearing minerals. These are pristine time capsules from the solar system’s birth.

- S-type (Silicaceous): Making up about 17% of the population, these are brighter and composed mainly of silicate rocks and nickel-iron metals. They are more common in the inner part of the main belt.

- M-type (Metallic): The relative rarities, these are composed almost entirely of nickel and iron. They are the likely cores of early protoplanets that were shattered in colossal impacts, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the differentiated interiors of larger bodies.

Beyond the Belt: The Dynamic Groups

The Main Belt is just the beginning. Asteroids are found in other dynamically significant regions, governed by the complex gravitational interplay of the planets, primarily Jupiter.

- Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs): These are the rock stars of planetary defense. Their orbits bring them close to Earth’s path around the Sun. They are subdivided into:

- Atiras: Orbits within Earth’s orbit.

- Atens: Orbits cross Earth’s orbit with a semi-major axis smaller than Earth’s.

- Apollos: Orbits cross Earth’s orbit with a semi-major axis larger than Earth’s.

- Amors: Orbits approach Earth’s from the outside but do not cross it.

Monitoring these is crucial for assessing impact risks. Programs like NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office keep a vigilant watch on these celestial neighbors.

- Trojans: This is one of the most brilliant demonstrations of orbital dynamics. Trojans are asteroids that share a planet’s orbit, residing in stable gravitational “sweet spots” known as Lagrange points, specifically the L4 and L5 points, which lead and trail the planet by 60 degrees. Jupiter has thousands of Trojans, but we now know Earth, Mars, Uranus, and Neptune have them too!

- The Hungarias, Cybeles, and Hildas: These are groups in the Main Belt locked in orbital resonances with Jupiter. For example, Hilda asteroids are in a 3:2 resonance, meaning they orbit the Sun three times for every two orbits of Jupiter. This resonance creates a stable, triangular pattern in their orbits.

Part 2: The Comets – Icy Wanderers from the Deep Freeze

If asteroids are the rocky inner-system rubble, comets are the icy messengers from the solar system’s outer darkness. Their spectacular, ethereal appearances have been recorded for millennia, often seen as omens. We now know they are something even more profound: ancient travelers carrying the original ingredients of the solar system.

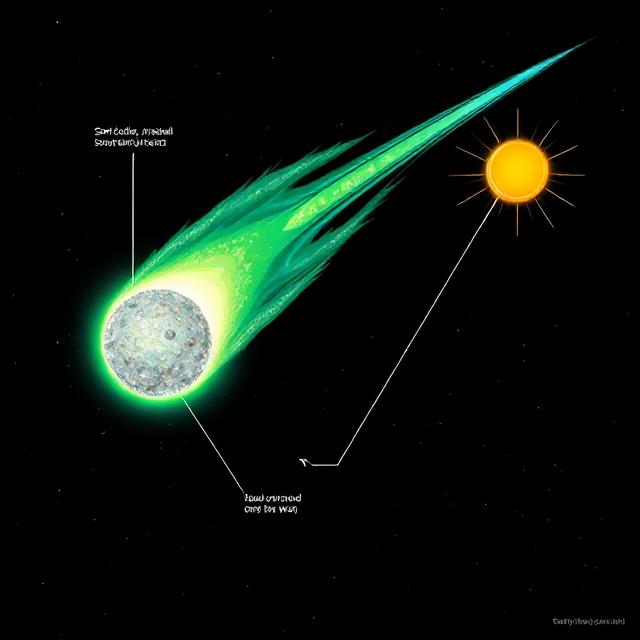

Anatomy of a Comet

A comet is often described as a “dirty snowball” or an “icy dirtball.” It’s a nucleus of ice, dust, and rocky material, typically only a few miles across. When a comet’s orbit brings it close to the Sun, the magic begins:

- The Nucleus: The solid, central core. This is the comet itself.

- The Coma: As the nucleus heats up, its ices sublimate (turn directly from solid to gas), releasing gas and dust that form a giant, fuzzy atmosphere around the nucleus, often millions of miles wide.

- The Dust Tail: The solar wind and radiation pressure push the dust particles away from the coma, forming a long, often broad and curved tail that glows by reflected sunlight. This is the most visually striking feature.

- The Ion Tail: The solar wind also ionizes the gas in the coma, creating a separate, straight tail that glows with a bluish light. This tail always points directly away from the Sun.

Where Do They Come From? The Cosmic Reservoirs

Comets originate in two primary reservoirs in the outer solar system:

- The Kuiper Belt: A vast, doughnut-shaped region beyond Neptune’s orbit, home to short-period comets (orbital periods less than 200 years), like Halley’s Comet. This is also the realm of dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris.

- The Oort Cloud: This is the ultimate deep freeze. A theoretical, giant spherical shell of icy objects surrounding our solar system, extending perhaps a light-year from the Sun. It contains trillions of comet nuclei. Long-period comets, with orbits taking thousands or even millions of years, are thought to originate here. A passing star or galactic tide can occasionally perturb one of these objects, sending it on a long fall into the inner solar system.

Comets are incredibly important to science because their ices are thought to preserve the original chemical conditions of the early solar system. There’s even a compelling theory, the “panspermia” hypothesis, that suggests comets could have delivered water and the basic organic building blocks of life to the early Earth.

Part 3: The Moons – More Than Just a Silent Companion

We often think of moons as simple companions to their planets, but this view is desperately outdated. The solar system’s moons are worlds in their own right, with some of the most extreme and interesting environments imaginable.

Captured vs. Formed In Place

Moons, or natural satellites, form in two primary ways:

- Co-formation: They form from a disk of gas and dust (an accretion disk) that surrounded the planet in its early days, much like the planets formed around the Sun. Jupiter’s Galilean moons (Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto) and Saturn’s Titan are believed to have formed this way.

- Capture: A planet’s gravity can “capture” a passing object, like an asteroid or comet, and pull it into a stable orbit. Mars’s small, lumpy moons, Phobos and Deimos, are likely captured asteroids. Neptune’s large moon, Triton, which orbits in the wrong direction (retrograde orbit), is almost certainly a captured Kuiper Belt Object.

A Tour of Marvelous Moons

The diversity of moons shatters the notion that they are barren, dead rocks.

- Io (Jupiter): The most volcanically active body in the solar system. Tidal heating from Jupiter’s immense gravity, locked in a resonant tug-of-war with other moons, flexes and heats Io’s interior, causing hundreds of active volcanoes to constantly resurface it.

- Europa (Jupiter): A smooth, icy world hiding a secret. Beneath its frozen crust, strong evidence points to a global subsurface ocean containing more than twice the water of Earth’s oceans. This makes Europa a prime target in the search for extraterrestrial life.

- Titan (Saturn): The only moon with a dense atmosphere and the only other body besides Earth with stable liquid on its surface—though its lakes and rivers are filled with liquid methane and ethane. It’s a complex world of hydrocarbon chemistry, with sand dunes and weather cycles eerily similar to Earth’s.

- Enceladus (Saturn): A small, bright moon that spews giant plumes of water vapor and ice crystals from a subsurface ocean near its south pole. These geysers contain organic molecules, making it another top candidate for astrobiology.

- Triton (Neptune): With its retrograde orbit and active cryogeysers (erupting nitrogen gas), Triton is a fascinating and geologically active captured world.

Part 4: The Grand Dance – Understanding Orbital Dynamics

So, what makes all these small bodies move? Why don’t they just crash into the Sun or fly off into interstellar space? The answer lies in the elegant, and sometimes chaotic, rules of orbital dynamics.

Gravity: The Cosmic Choreographer

Isaac Newton revealed that gravity is the force that binds the solar system. Every object with mass attracts every other object. Your phone is gravitationally attracted to you, and an asteroid in the belt is attracted to Jupiter. The planets orbit the Sun because the Sun’s immense gravity is constantly pulling them inward, while their forward motion (their inertia) tries to carry them away in a straight line. The balance between these two forces creates a stable, elliptical orbit.

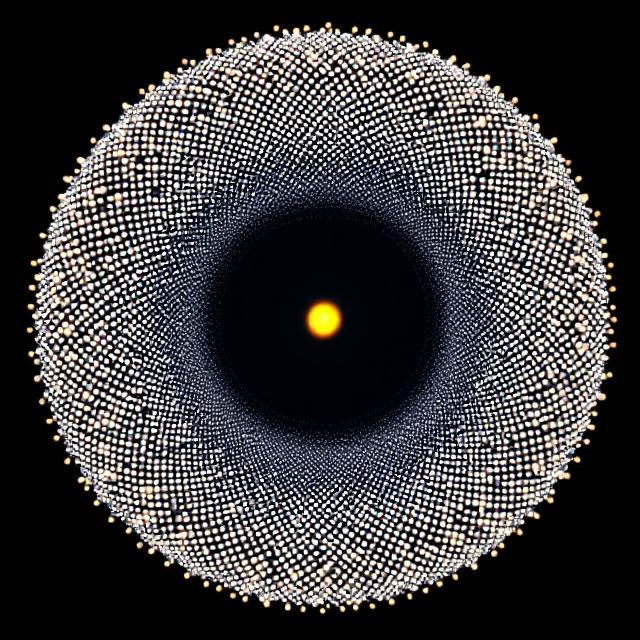

Orbital Resonances: The Music of the Spheres

This is one of the most beautiful concepts in celestial mechanics. An orbital resonance occurs when two orbiting bodies exert a regular, periodic gravitational influence on each other due to their orbital periods being in a ratio of two small integers.

Think of it like pushing a child on a swing. If you push at just the right moment in the swing’s cycle, you add energy and the swing goes higher. If you push at the wrong time, you disrupt the motion.

- The Kirkwood Gaps: In the Asteroid Belt, there are clear gaps where very few asteroids are found. These correspond to locations where an asteroid would have an orbital period that is a simple fraction (e.g., 1/2, 1/3, 2/5) of Jupiter’s period. Jupiter’s repeated gravitational “pushes” at the same point in the asteroid’s orbit eventually destabilize it, causing it to be ejected from that region.

- The Pluto-Charon System: Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, are locked in a perfect tidal lock, but they also share a 1:1 orbital resonance with four smaller moons (Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra). Their orbits are incredibly stable and predictable because of this complex resonance.

Tidal Forces: The Cosmic Squeeze

Tidal forces are the result of the difference in gravitational pull across a body. The side of a moon closer to its planet feels a stronger pull than the far side. This stretches the moon and creates internal friction, generating heat. This tidal heating is the engine that powers the volcanoes on Io and likely keeps the subsurface oceans of Europa and Enceladus from freezing solid.

Perturbations and Chaos

Over long timescales, the solar system is a chaotic system. The gravitational pull of the planets, especially the gas giants, constantly “perturbs” or slightly alters the orbits of small bodies. A tiny nudge from Jupiter can:

- Fling an asteroid from the belt into the inner solar system, turning it into a Near-Earth Asteroid.

- Send a Kuiper Belt Object inward to become a short-period comet.

- Eject an object from the Oort Cloud, sending it on a multi-million-year journey toward the Sun.

This gravitational pinball is a constant process, reshaping the small-body populations of our solar system.

Why Should We Care? The Practical Implications

This isn’t just abstract science. Understanding small bodies and their dynamics has direct, tangible consequences for humanity.

- Planetary Defense: The dinosaurs learned the hard way that asteroids can impact Earth. Studying the orbits and compositions of NEAs is our first line of defense. Missions like NASA’s DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) have proven we can actively alter an asteroid’s trajectory, a crucial capability for protecting our planet.

- The History of Our Solar System: These objects are the building blocks that never made it. By studying them—like the OSIRIS-REx and Hayabusa2 missions that returned samples from asteroids—we are reading the original recipe for planets, including our own.

- The Future of Space Resources: Asteroids are floating mines of precious resources. M-type asteroids contain vast amounts of iron, nickel, and cobalt. Some even contain platinum-group metals. In the future, asteroid mining could provide the raw materials for building structures in space, reducing the need to launch everything from Earth’s deep gravity well.

- The Search for Life: The subsurface oceans of Europa and Enceladus are among the most promising places to look for life beyond Earth. Comets may have seeded Earth with the water and organic compounds necessary for life to begin. To understand the potential for life in the universe, we must realize these small bodies.

FAQ: Your Questions About Solar System Small Bodies, Answered

1. What is the main difference between an asteroid and a comet?

The main difference lies in their composition and resulting appearance. Asteroids are primarily rocky and metallic, leftover from the inner solar system’s formation. They are often found in the Asteroid Belt and do not develop a visible atmosphere or tail. Comets, on the other hand, are “dirty snowballs” made of ice, dust, and rock, originating from the cold outer solar system. When a comet’s orbit brings it close to the Sun, its ices vaporize, creating a glowing coma (atmosphere) and the iconic, spectacular tails that can stretch for millions of miles.

2. Can we really deflect a dangerous asteroid?

Yes, we are actively developing and testing this technology. In 2022, NASA’s DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission successfully proved the concept by crashing a spacecraft into a small asteroid called Dimorphos and measurably changing its orbit. This “kinetic impactor” technique is one of the most promising methods for planetary defense. The key is finding potential threats decades in advance, so even a small nudge can be enough to make a future impact miss Earth entirely.

3. Why are moons like Europa and Enceladus so important to scientists?

Europa (orbiting Jupiter) and Enceladus (orbiting Saturn) are considered top priorities in the search for extraterrestrial life because they host vast subsurface liquid water oceans beneath their icy crusts. On Earth, wherever we find water, energy, and organic compounds, we find life. Data from spacecraft shows that these moons have all three ingredients. The plumes of water vapor erupting from Enceladus even contain complex organic molecules, making them prime targets for future missions designed to look for signs of life.

4. What exactly are “orbital resonances” and why do they matter?

An orbital resonance is a kind of gravitational “synchronization” where two orbiting bodies exert a regular, repeating influence on each other because their orbital periods are a ratio of small whole numbers (e.g., 2:1 or 3:2). Think of it like pushing a child on a swing at just the right time to make them go higher.

They matter because resonances can create stable patterns or zones of instability. For example, Jupiter’s resonances clear out the Kirkwood Gaps in the Asteroid Belt, while stable resonances allow Trojan asteroids to share an orbit with Jupiter. Resonances protect some objects and eject others, fundamentally shaping the structure of our solar system.

5. Did comets really bring water to Earth?

This is a leading scientific theory, known as the “late heavy bombardment” hypothesis. While Earth formed too close to the Sun to initially retain much water, it’s believed that millions of comets and water-rich asteroids pummeled our planet billions of years ago. Analysis of comet water (via its deuterium/hydrogen ratio) shows that for some comets, it is a close match to Earth’s water. It’s likely that a significant portion of our oceans, and the organic building blocks of life, were delivered by these ancient icy impactors.

Conclusion: A Living, Breathing Solar System

The next time you look up at the night sky, see it not as a static painting, but as a vibrant, dynamic, and ever-changing ecosystem. The silent points of light are planets, yes, but between and beyond them is a swirling ballet of countless smaller worlds.

Asteroids, comets, and moons are not mere afterthoughts. They are the storytellers, the architects, and the wanderers. They are the keys to our past and the gateways to our future. They remind us that our solar system is a living, breathing entity, governed by the beautiful, predictable, yet occasionally chaotic, laws of physics. It’s a cosmic dance that has been ongoing for 4.6 billion years, and we are just now learning the steps.