We’ve all been there. Staring at the night sky, overwhelmed by a simple, profound question: What is everything made of?

We learned in school that everything is made of molecules, which are made of atoms. Dig deeper, and you find a nucleus of protons and neutrons orbited by electrons. Deeper still, you find that protons and neutrons are made of even smaller particles called quarks. For decades, we’ve called these quarks and electrons fundamental particles—the final, indivisible building blocks of nature.

But what if that’s not the end of the story? What if these point-like particles aren’t points at all?

Welcome to the wild, wonderful, and wonderfully weird world of string theory. It’s a framework that proposes a radical answer: at the heart of every particle, there is a tiny, vibrating, one-dimensional loop of energy called a string.

Imagine the universe isn’t made of dots, but of unimaginably small strings. And just like a single violin string can vibrate in different ways to produce all the notes of a scale—a C, a G, a high A—a fundamental string can vibrate in different patterns to produce all the different particles we see.

The electron is a string vibrating one way. A quark is the same string vibrating another way. The photon (carrier of light) is that string vibrating in yet another pattern.

In this view, the entire universe is a cosmic symphony, composed on these tiny, vibrating strings. It’s a beautiful, powerful idea. But is it true? And what does it all mean?

Let’s untangle the knots of this revolutionary theory together.

The Cosmic Problem: Why We Needed a New Theory

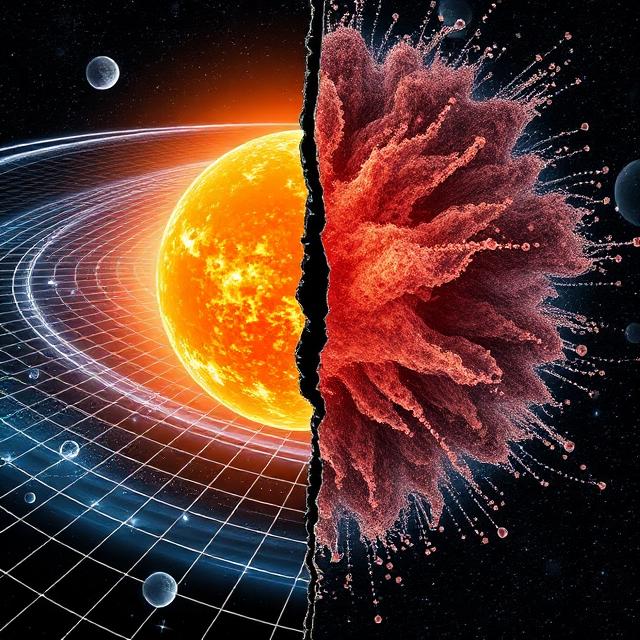

To understand why string theory is such a big deal, we first need to understand the problem it’s trying to solve. For about a century, physics has been standing on two towering, yet fundamentally opposed, pillars.

Pillar 1: General Relativity – The Theory of the Very Big

Albert Einstein’s masterpiece. This theory describes the force of gravity as the curvature of spacetime. A massive object like the sun warps the space and time around it, and Earth follows that curvature—that’s what we call orbit.

In a nutshell, General Relativity is the rulebook for gravity and the large-scale structure of the universe.

General Relativity is breathtakingly accurate. It predicts black holes, the bending of light (gravitational lensing), and the expansion of the universe itself. It’s the law of the cosmos, governing planets, galaxies, and the universe at large.

Pillar 2: Quantum Mechanics – The Theory of the Very Small

While Einstein was looking at the stars, other physicists were peering into the atom. What they found was a bizarre, probabilistic world that defies common sense. Quantum Mechanics is the rulebook for the other three fundamental forces: electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force.

In this realm, particles are also waves, things can be in two places at once (superposition), and you can’t know both a particle’s position and momentum perfectly (the Uncertainty Principle). It’s a fuzzy, chaotic, and incredibly successful theory that underpins all of modern chemistry, electronics, and nuclear physics.

In a nutshell, Quantum Mechanics is the rulebook for particles and the small-scale world.

The Collision: A Universe at War with Itself

So, we have two incredibly successful theories. The problem? They are utterly, completely incompatible.

- General Relativity is smooth, continuous, and deterministic. It paints a picture of a flexible, but well-behaved, fabric of spacetime.

- Quantum Mechanics is jerky, discrete, and probabilistic. It’s a world of wild fluctuations and uncertainty.

This conflict becomes catastrophic in extreme environments where both gravity and quantum effects are significant—like at the center of a black hole, or at the moment of the Big Bang. Here, our equations break down. They produce nonsense answers, like probabilities greater than 100% or infinite densities. Physicists call this “a theory of quantum gravity,” and finding it is the holy grail of modern physics.

This is the chasm that string theory attempts to bridge.

The “Aha!” Moment: So, What Is a String?

The central idea of string theory is deceptively simple. Forget zero-dimensional points. The most fundamental entity is a one-dimensional filament of energy—a string.

These strings are unimaginably small. If an atom were enlarged to the size of our solar system, a string would be about the size of a tree on Earth. This is why we can’t hope to see them directly with particle colliders like the Large Hadron Collider.

But their size isn’t the most important part. It’s what they do.

The Universe’s Ultimate Instrument

A violin string can only vibrate in certain, discrete ways—what we call harmonics or resonances. It can’t just vibrate any old way; the ends are fixed. These allowed vibrations produce specific notes.

A fundamental string is the same. It has a set of allowed, resonant vibrational patterns. And here’s the magic:

- One specific pattern of vibration gives rise to the properties of a graviton, the hypothetical quantum particle that carries the gravitational force.

- Another distinct pattern gives rise to the properties of a photon, the particle of light.

- Another pattern creates an electron.

- Yet another creates a quark.

In this stunningly elegant picture, every particle is a manifestation of the same underlying string, just “playing a different note.” The diversity of the universe comes not from different types of “stuff,” but from different kinds of vibrations of the same basic “stuff.”

This solves the gravity problem at a stroke. Gravity isn’t awkwardly glued onto the theory; it’s inherently part of the string’s musical repertoire. The graviton emerges naturally from the vibrations, seamlessly weaving gravity into the quantum world. For the first time, we have a single framework that describes all forces and all matter.

The Catch: The Price of Unification is Extra Dimensions

Now we get to the part that makes string theory controversial and, frankly, mind-blowing. The mathematics of string theory only works if the universe has more than the three spatial dimensions (length, width, height) and one time dimension we experience.

For the equations to be consistent and avoid nonsense, string theory requires extra spatial dimensions.

How Many Dimensions? It Depends.

The original version of string theory (Bosonic String Theory) required 26 dimensions! A more modern and realistic version, called Superstring Theory, brought it down to a more “manageable” 10 dimensions (9 of space, 1 of time).

So, where are these extra six dimensions? Why don’t we see them?

The Compactification Solution: It’s All Curled Up

Physicists propose that these extra dimensions are compactified, or curled up into an infinitesimally small size. To understand this, think of a garden hose.

From a distance, a hose looks like a one-dimensional line. You can only move along its length. However, if you look closely, you’ll see that it has a second dimension—a circular cross-section. This dimension is “compactified,” or curled up so small that it’s invisible to the naked eye.

The extra six dimensions in string theory are thought to be curled up into a complex, tiny shape at every single point in our familiar 3D space. This shape is known as a Calabi-Yau manifold. This is both a feature and a bug. It provides a potential mechanism for explaining why our universe has the laws it does, but it also leads to a major criticism of string theory: the “landscape” problem.

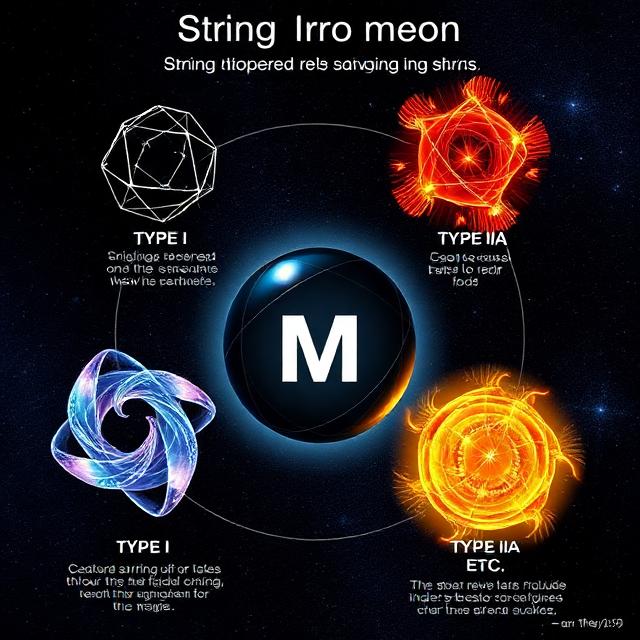

The Five Flavors and M-Theory: A Theory of Theories

As if extra dimensions weren’t strange enough, physicists in the 1980s and 90s found not one, but five distinct, self-consistent versions of superstring theory. They were named Type I, Type IIA, Type IIB, and two flavors of Heterotic string theory (E8xE8 and SO(32)).

This was deeply embarrassing. If string theory is the one “Theory of Everything,” why are there five of them?

The Second Revolution: M-Theory to the Rescue

In 1995, physicist Edward Witten sparked a second revolution. He showed that these five theories were not rivals, but different facets of a single, deeper, more fundamental theory, which he called M-Theory.

M-Theory is still poorly understood, but it came with a bombshell: it requires 11 dimensions (10 of space, 1 of time).

So, what is “M” for? Witten was coy about it, suggesting it could stand for Magic, Mystery, or Matrix. But it’s also often associated with Membrane. M-Theory suggests that strings are not the only fundamental objects; there could also be higher-dimensional objects called branes (short for membranes).

A point-particle is a 0-brane. A string is a 1-brane. M-Theory introduces 2-branes (membranes), 3-branes, and so on, all the way up to 9-branes. Our entire universe could be a giant 3-brane (a 3-dimensional membrane) floating in a higher-dimensional “bulk.” This idea has led to fascinating cosmological models, including new explanations for the force of gravity’s relative weakness.

The Controversy: The Great String Theory Debate

String theory is not without its fierce critics. It’s important to understand the main points of contention.

1. The Lack of Experimental Evidence (The Biggest Critique)

This is the central problem. String theory operates at energy scales far beyond the reach of any current or conceivable particle accelerator. There is, as of yet, no direct experimental test that can confirm or refute it. For many, this pushes it from physics into the realm of philosophy or mathematics.

2. The Landscape Problem

The different ways to curl up the extra dimensions (the different Calabi-Yau shapes) could lead to a staggering number of possible universes—perhaps 10^500 or more. Each universe would have its own laws of physics. This “landscape” of possibilities means that string theory may not predict our unique universe, but rather a multiverse where every possible law exists somewhere. If a theory can predict anything, does it really predict anything at all?

3. Not The Only Game in Town

String theory is the most popular candidate for a theory of everything, but it’s not the only one. Loop Quantum Gravity is its main rival, which tries to quantize space itself rather than proposing strings. It has its own challenges but is favored by some who see string theory as an untestable, mathematical detour.

Why We Can’t Give Up: The Profuse Promise of String Theory

Despite the controversies, the allure of string theory remains powerful because of its profound successes.

- A Natural Home for Gravity: It is the only framework that naturally incorporates gravity into the quantum world. It doesn’t just add gravity; gravity is a necessary consequence.

- Unification of All Forces and Matter: It provides a truly unified vision of reality, where all particles and forces are different expressions of a single entity.

- Explaining Black Holes: String theory has been used to calculate the entropy of certain black holes, a problem that had stumped physicists for decades. This is considered one of its major triumphs.

- A “Theory of Physics Itself”: It doesn’t just describe what happens in the universe; it potentially explains why the universe has the rules it does—why the electron has its specific mass, why we have three spatial dimensions, etc.

String Theory and You: What Does It All Mean?

You might be thinking, “This is fascinating, but what does it have to do with my daily life?”

In a practical, technological sense? Nothing right now. You won’t see a “string theory” app on your phone.

But in a deeper, philosophical sense, it has everything to do with us. String theory is the current frontier of humanity’s oldest quest: to understand our place in the cosmos. It’s a story we are still writing, a puzzle we are still solving. It challenges our perception of reality, suggesting that the universe is far stranger, more elegant, and more interconnected than we ever dreamed.

It reminds us that the universe may not be a collection of separate, solitary points, but a resonant, dynamic, and unified whole—a cosmic symphony, and we are all part of its music.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is string theory proven?

A: No. String theory is a highly sophisticated and mathematically consistent framework, but it remains a theoretical proposal. It has not yet been verified by experiment.

Q: Can string theory be tested?

A: Not directly with current technology. However, physicists are looking for indirect evidence. This could include finding evidence for supersymmetry at particle colliders, discovering gravitational waves from the early universe that hint at extra dimensions, or observing unexpected properties of black holes.

Q: What is the difference between string theory and the Theory of Everything?

A: A “Theory of Everything” (TOE) is the ultimate goal—a single framework that explains all physical aspects of the universe. String theory is the leading candidate for a TOE.

Q: How long until we know if string theory is true?

A: There’s no way to know. It could be decades, centuries, or we may never have the technological capability to test it definitively. The journey of discovery is ongoing.