Imagine a cosmic engine so powerful it can blast searing gas and radiation across millions of light-years. A force so immense it can halt the birth of stars in its path, yet paradoxically, create the perfect conditions for future stellar nurseries. This isn’t science fiction. At the heart of almost every large galaxy, including our own Milky Way, lies a supermassive black hole. And some of these black holes are the universe’s ultimate sculptors, firing vast beams of energy—known as jets—that directly shape the fate of their home galaxies and beyond.

For decades, these jets were cosmic mysteries, faint streaks in radio telescope images. Today, we understand they are fundamental to answering one of astronomy’s biggest questions: Why do galaxies look the way they do, and what controls their growth? This is the story of how the universe’s most destructive phenomena—black hole jets—are also essential architects of cosmic order.

The Heart of Darkness: Not So Black After All

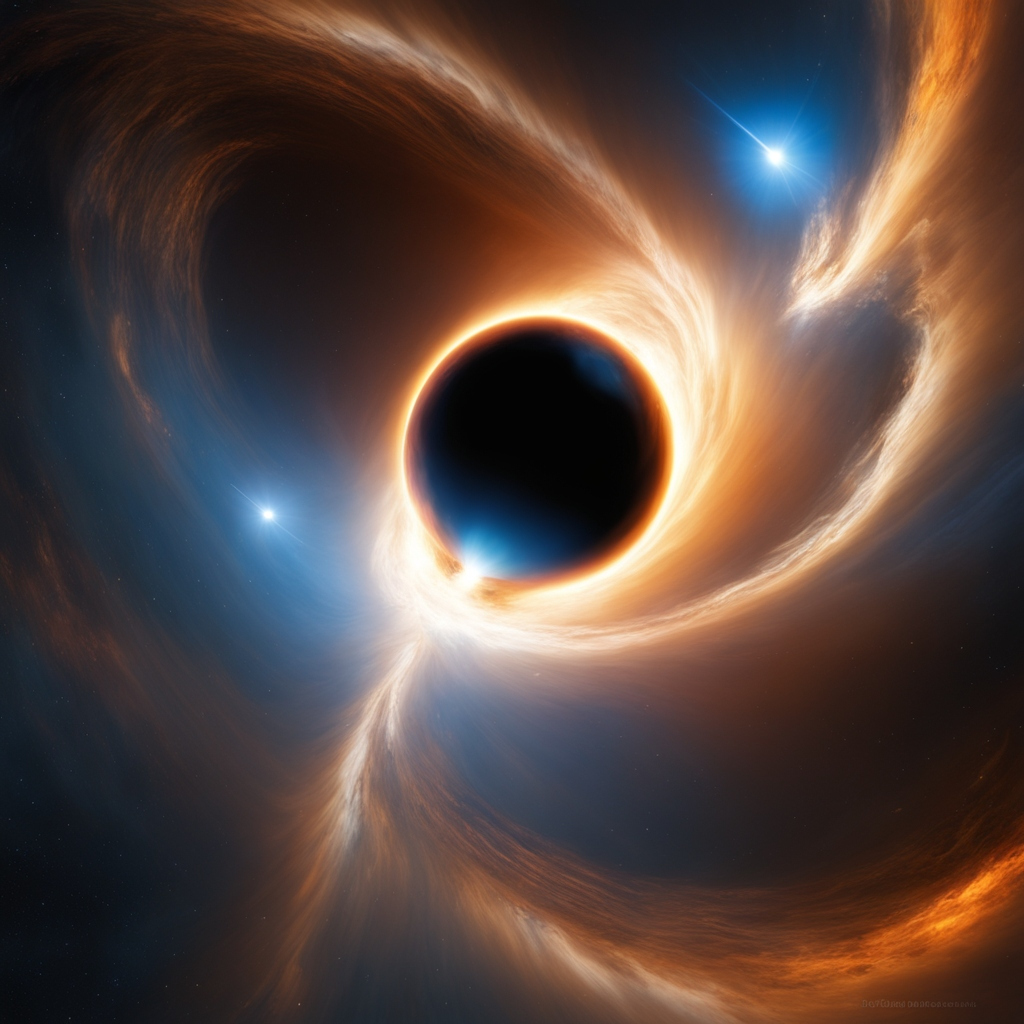

Let’s start with a correction. The term “black hole” conjures an image of a simple, greedy vacuum cleaner in space. In reality, the region around a supermassive black hole (millions to billions of times the Sun’s mass) is the most dynamic and energetic environment in the universe.

When a black hole actively feeds on surrounding gas, dust, and stars, this material doesn’t just vanish. It spirals inward, forming a superheated, magnetized disk called an accretion disk. Temperatures here can reach millions of degrees, glowing fiercely across the electromagnetic spectrum. This entire system is known as an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN).

But the real magic happens at the poles. Some of the infalling material, along with immense magnetic fields, gets channeled and accelerated outward at nearly the speed of light. These are the relativistic jets. They can extend far beyond their host galaxy, often for hundreds of thousands of light-years, sometimes dwarfing the galaxy itself.

Key Insight: A black hole isn’t just a pit. It’s a transformative engine. It converts gravitational energy into radiation and kinetic energy on a staggering scale. A single jet can output more energy in a second than our Sun will in its entire 10-billion-year lifetime.

The Anatomy of a Cosmic Particle Beam

So, what exactly are these jets made of? They’re not simple flames or geysers. They are highly collimated (pencil-straight) beams of:

- Plasma: A soup of charged particles—electrons and protons.

- Magnetic Fields: Woven through the plasma, providing structure and acceleration.

- Radiation: From radio waves to high-energy gamma rays, emitted as particles spiral along magnetic field lines.

Their straightness over such vast distances is one of their most puzzling features. It’s like firing a laser pointer from Earth and having it stay perfectly straight past the Moon. This is where the black hole’s incredible spin and the physics of magnetohydrodynamics (a fancy word for how magnetic fields and plasma interact) come into play, acting as a cosmic focusing nozzle.

We observe these jets primarily in two ways:

- Radio Telescopes (like the VLBA or ALMA) capture the synchrotron radiation from electrons whizzing in magnetic fields, revealing their magnificent, often lobed structures.

- X-ray Observatories (like Chandra) see where jets smash into intergalactic gas, creating shock waves that heat material to millions of degrees.

As NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory team notes, “Jets from supermassive black holes can inject huge amounts of energy into their surroundings and influence the rate of formation of stars in galaxies.” (Source: Chandra.Harvard.edu)

The Galactic Sculptor: How Jets “Quench” Star Formation

Here’s where the plot thickens. Galaxies need cold gas to form stars. Gravity pulls gas clouds together until they collapse, ignite, and become stars. So, what happens when a jet from the central black hole plows through this galactic reservoir?

The effect is transformative and, for star formation, often destructive. This process is known as “AGN feedback” or “quenching.”

- Heating the Gas Pool: The jets dump colossal energy into the galaxy’s halo of hot gas. Think of it as blowing a giant, continuous hair dryer into a cloud of cold, star-forming mist. The gas gets too hot and energetic to clump together under gravity. Star formation grinds to a halt.

- Blowing Out the Fuel: In more dramatic episodes, jets can literally blow gas clean out of the galaxy. This is a galactic outflow. Observations have shown massive winds of gas, triggered by jet activity, streaming out of galaxies at speeds of millions of miles per hour. This strips the galaxy of its future stellar fuel.

This sounds purely destructive. And it is. But this destruction serves a critical cosmic purpose.

Without this “quenching” mechanism, our cosmological simulations show that galaxies would continue to feed, grow uncontrollably, and form stars far beyond what we observe. They would become monstrously large, blue, star-forming disks. Yet, we see a universe filled with a diversity of galaxies, including many “red and dead” elliptical galaxies where star formation ceased long ago. Black hole jets are the leading candidate for the “off switch.”

As Dr. Brian McNamara, a leading researcher in this field, stated in a study published in Nature, “The energy delivered by these jets can be enough to shut down star formation by heating the gas that would otherwise cool to form stars. It’s a case of the black hole regulating the growth of its own host galaxy.” (Related Research on AGN Feedback)

The Paradox: How Destruction Can Also Foster Creation

Now for the beautiful paradox. While jets can quench star formation on a galactic scale, they can also trigger it locally. This dual role is what makes them such fascinating sculptors.

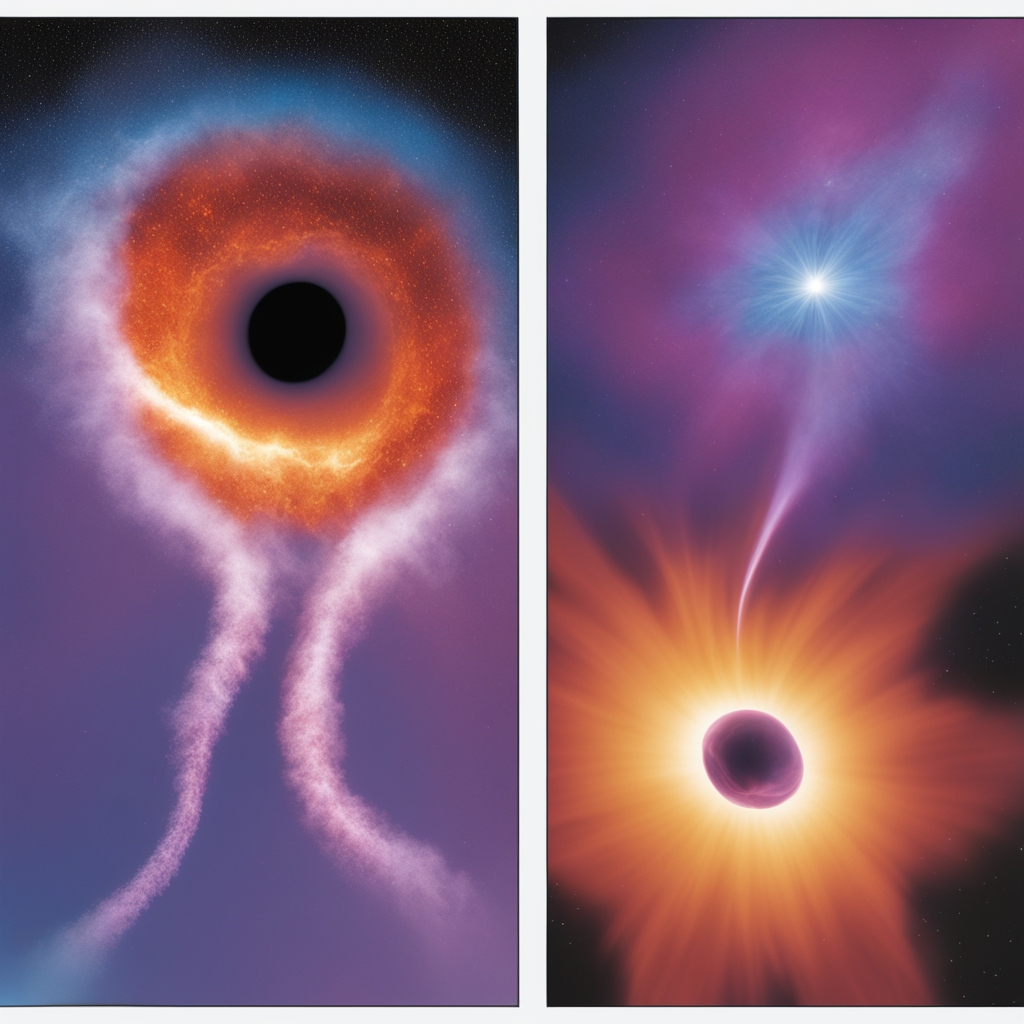

When the tip of a jet, often ending in a massive radio lobe, plows into a dense cloud of intergalactic gas, it doesn’t just heat it uniformly. It creates powerful shock waves and compresses the gas at the edges of these lobes.

Imagine pushing a giant snowplow. In front of the blade, snow is scattered and destroyed. But along the sides, snow can be compressed into denser, more consolidated piles. Similarly, the immense pressure from a jet’s shock wave can squeeze galactic or intergalactic gas clouds, causing them to collapse under their own gravity and—counterintuitively—spark new star formation.

Astronomers have found compelling evidence of this “jet-induced star formation” in systems like the famous galaxy Minkowski’s Object. Here, a jet from a neighboring galaxy is slamming into a gas cloud, and we see a trail of bright, young stars forming in the jet’s wake.

This creates a stunning narrative: the same force that shuts down star formation in the galactic core can simultaneously create stellar nurseries on its remote outskirts. The black hole is not just a destroyer; it’s a cosmic landscaper, shaping where and when stars can be born.

The Cosmic Feedback Loop: A Symbiotic Relationship

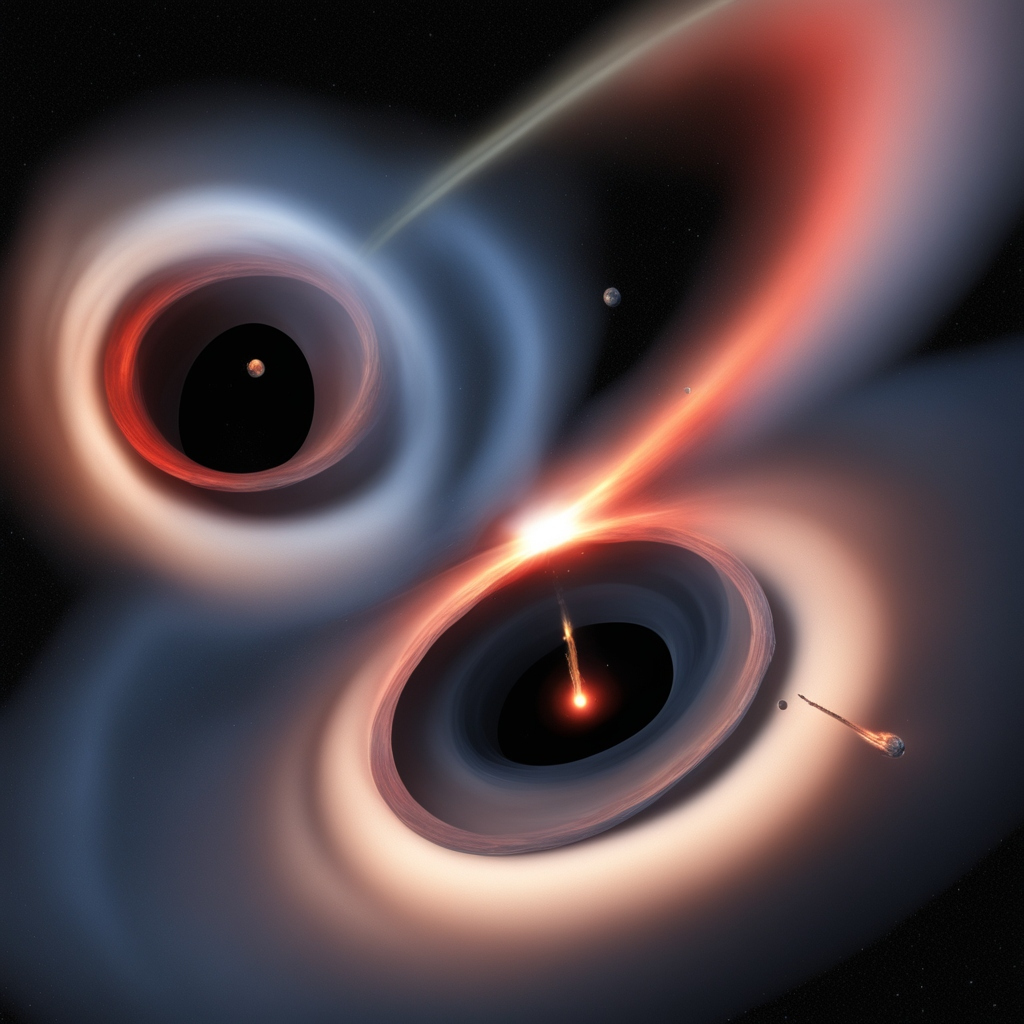

This leads us to perhaps the most profound discovery in modern astrophysics: the symbiotic relationship between a galaxy and its central black hole. They don’t just coexist; they co-evolve.

How does this work? It’s a self-regulating cycle, a cosmic feedback loop:

- Feeding Frenzy: Two galaxies merge, or a large influx of gas flows toward the center. This feeds the supermassive black hole, igniting the AGN and turning on the jets.

- Energetic Feedback: The jets blast energy into the surrounding galaxy, heating and ejecting the gas reservoir.

- Starvation: With its fuel supply cut off, the black hole itself begins to starve. The AGN activity dims, and the jets weaken or turn off.

- Cooling and Accretion: Over hundreds of millions of years, the hot halo gas slowly cools and can once again fall toward the center…

- Repeat: …potentially reigniting the black hole and starting the cycle anew.

This elegant loop explains a fundamental correlation observed across the universe: the M-σ relation. The mass of a galaxy’s central bulge is tightly correlated with the mass of its supermassive black hole. A bigger galaxy has a bigger black hole. This is strong evidence that their growth histories are intimately linked—the black hole’s jets regulate the galaxy’s growth, and the galaxy’s gas supply regulates the black hole’s activity.

Beyond the Host: Jets as Intergalactic Weather Makers

The influence of these jets doesn’t stop at the galactic border. They shape the very fabric of the intergalactic medium (IGM)—the thin, hot gas that fills the space between galaxies, especially within massive galaxy clusters.

Galaxy clusters are the universe’s largest gravitationally bound structures, containing thousands of galaxies swimming in a sea of superheated plasma (10+ million degrees Celsius). Left to its own devices, this gas should rapidly cool, fall into the central galaxies, and form trillions of stars. But we don’t see that.

Why? The central galaxy’s black hole acts as a “cosmic thermostat.” Its jets pump energy into the cluster gas, preventing it from cooling catastrophically. Chandra X-ray images show gigantic cavities and ripples in the hot gas of clusters like Perseus and Virgo—direct imprints of jets punching through and inflating bubbles of relativistic particles.

“These bubbles are a testament to the repeated outbursts from the central black hole,” explains a report from the Hubble Space Telescope team studying the Perseus Cluster. “They redistribute the cluster’s hot gas, effectively heating it and preventing a cooling flow that would result in excessive star formation.” (Source: HubbleSite.org)

This means black hole jets are crucial for regulating the growth of not just their host galaxy, but entire clusters of galaxies, maintaining the delicate thermal balance of the largest structures in the cosmos.

The Unanswered Questions & The Future of Discovery

Despite the revolutionary progress, this field is alive with mystery.

- The Trigger Mechanism: What exactly flips the switch to turn a jet on? Is it a specific type of accretion, or the black hole’s spin?

- Jet Composition: We know there are electrons and magnetic fields, but how much of the jet’s power is in invisible protons? This is a key unknown.

- The Role of Dwarf Galaxies: Do smaller black holes in smaller galaxies have a similar, scaled-down effect? This is a frontier for telescopes like JWST.

- Connecting the Scales: How do we perfectly link the micro-physics near the black hole’s event horizon (studied by the Event Horizon Telescope) to the macro-physics of galactic evolution?

The next generation of tools is poised to answer these questions. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will peer through dust to see the early universe, watching black holes and their host galaxies grow together in their infancy. Radio astronomy arrays like the Next Generation VLA (ngVLA) will map jet structures with unprecedented detail. And continued multi-wavelength studies—combining data from radio, optical, X-ray, and gamma-ray observatories—will give us a holistic view of these complex systems.

Conclusion: Our Place in a Shaped Universe

We began with an image of pure destruction: a black hole firing a deadly beam across the cosmos. We end with a vision of delicate balance. These jets are the universe’s primary tool for regulating its own growth. They prevent galaxies from becoming bloated giants, they stir the pots of galaxy clusters, and they even carve out niches for new stars to form.

This story connects the infinitesimally small—the physics near an event horizon—to the grandest scales of the cosmic web. It reveals a universe not of random chaos, but of self-regulating cycles, where even the most violent phenomena are woven into the tapestry of creation.

The next time you look up at a dark, starry sky, consider this: the majestic spiral of Andromeda, the calm ellipse of a distant red galaxy, and the vast, empty spaces between clusters have all been shaped, in part, by the invisible hearts of darkness at their centers. They are the cosmic storms that both give and take away, the eternal sculptors in the dark.

FAQ Section

1. What exactly are black hole jets?

Black hole jets are narrow, incredibly powerful beams of plasma and radiation that shoot out from the poles of some supermassive black holes at nearly the speed of light. They form when material from the black hole’s accretion disk is channeled by intense magnetic fields and launched outward. These jets can extend for hundreds of thousands of light-years, far beyond their host galaxy.

2. If black holes pull everything in, how do they shoot jets out?

This is a common point of confusion! The jets don’t come from inside the black hole’s event horizon (from which nothing can escape). Instead, they’re launched from the accretion disk—the swirling, superheated ring of gas and dust around the black hole. The incredible gravitational energy of the infalling material is converted, via complex magnetic processes, into a focused outward beam. It’s the black hole’s gravity powering an engine, not the black hole itself “leaking.”

3. How can something so destructive help “grow” a galaxy?

It’s all about regulation, not just destruction. Without this mechanism, galaxies would consume gas too quickly, forming stars in an uncontrolled burst and then fizzling out. Jets provide “AGN feedback“: they heat and redistribute gas, slowing down star formation to a sustainable rate. This prevents the galaxy from burning through its fuel, allowing for longer, more structured growth. In some cases, they even compress gas clouds to trigger new star formation in their wake. Think of it as a cosmic gardener who both prunes and plants.

4. What is “AGN Feedback”?

AGN (Active Galactic Nucleus) Feedback is the process by which the energy released from an active black hole—via jets and radiation—affects its surrounding environment. This feedback can heat cold, star-forming gas (suppressing star formation), drive massive galactic winds (removing fuel), or even compress gas to trigger localized star formation. It’s the primary mechanism by which black holes and their host galaxies communicate and co-evolve.

5. Do we have real observations of this happening?

Absolutely! Landmark observations come from telescopes like the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. For example:

- Chandra has imaged giant cavities and ripples in the hot gas of galaxy clusters (like the Perseus Cluster), carved out by black hole jets. (NASA Chandra Observatory)

- Hubble and other telescopes have studied objects like “Minkowski’s Object,” where a jet from a nearby galaxy appears to be triggering a burst of star formation as it plows into a gas cloud. These are considered “smoking gun” evidence of jet-induced creation.

6. Does our own Milky Way galaxy have these jets?

Our galactic center houses a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A*, but it is currently relatively quiet (dormant or “quiescent”). It is not actively accreting large amounts of material and therefore is not producing powerful, large-scale jets like those seen in active galaxies. However, astronomers have detected faint, intermittent radio and X-ray emissions suggesting past activity and possibly smaller-scale outflows. Our galaxy likely experienced stronger AGN feedback in its distant past.

7. Why is understanding this important for cosmology?

Black hole jets are a crucial piece of the galaxy formation puzzle. Our simulations of the universe only match the real cosmos we see—with the correct distribution of galaxy sizes, shapes, and star formation rates—when we include the regulating effects of AGN feedback. They explain why we don’t see overly massive galaxies and how the most massive galaxies transition from blue, star-forming spirals to “red and dead” ellipticals. Essentially, they help us understand the lifecycle of galaxies across cosmic time.

8. What tools are scientists using to study this phenomenon?

This is a truly multi-wavelength effort:

- Radio Telescopes (ALMA, VLA): Map the structure of the jets and cold gas.

- X-ray Observatories (Chandra, XMM-Newton): Observe the superhot gas heated by jet interactions.

- Optical/UV Telescopes (Hubble, James Webb Space Telescope): Study star formation histories and galactic structures.

- Theoretical Models & Supercomputers: Run complex simulations to understand the physics connecting the small-scale jet to large-scale galactic effects.