Look up at the night sky. If you’re far from city lights, you see the timeless, dusty band of the Milky Way, the steadfast North Star, and the wandering planets. But increasingly, you might also see something new: a faint, steady procession of stars moving in a straight line, one after another. These are not stars. They are the vanguards of a new space age, the physical manifestations of a multi-billion-dollar battle being waged not on Earth, but in the shell of space just above it.

This is the race for global satellite internet supremacy. In one corner, Starlink (SpaceX), the fast-moving, rule-breaking disruptor already serving over 3 million users. In another, OneWeb, the phoenix that rose from bankruptcy with global government backing. And in the third, Project Kuiper (Amazon), the sleeping giant, armed with near-limitless resources and a relentless logistical machine, is yet to launch its first operational satellite.

This isn’t just a tech rivalry; it’s a story of different visions for our connected future. Let’s untangle the constellations.

The Contenders: Origins, Philosophies, and Pocketbooks

Starlink: The “Move Fast and Break Things” Maverick

Born from Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Starlink’s origin story is inextricably linked to a grander vision: funding Mars colonization. The logic was simple: create a profitable satellite internet business to fuel the expensive rockets and starships needed for interplanetary travel. This gives Starlink a unique, almost relentless drive.

From the start, SpaceX leveraged its own reusable Falcon 9 rockets, giving it an unprecedented cost advantage and launch cadence. Their philosophy has been agile, iterative, and sometimes controversial. They started launching prototypes (Tintin A & B) in 2018, quickly followed by generations of operational satellites, learning and upgrading with each batch. As noted by SpaceNews, this approach allowed them to “iterate on satellite design rapidly,” a stark contrast to traditional, slower aerospace cycles. They’ve faced astronomers’ ire over brightness, concerns about space debris, and regulatory skirmishes, but they’ve also connected remote communities, aided in disaster response in Ukraine and Hawaii, and fundamentally changed the conversation about broadband availability.

OneWeb: The “Global Partnership” Player

OneWeb’s story is a corporate drama. Founded in 2012 by Greg Wyler, its goal was similar: global connectivity. However, its path was more traditional—securing massive funding, partnering with established aerospace giants like Airbus for satellites, and contracting launch services from others (initially Soyuz rockets). It raced neck-and-neck with SpaceX to secure early FCC approvals.

Then, in March 2020, just as the world locked down and the need for connectivity skyrocketed, OneWeb filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, a victim of its capital-intensive model and the pandemic’s economic shock. Its salvation was geopolitical. A consortium led by the UK Government and Bharti Global (India’s telecom giant) acquired it. Later, Eutelsat, the European satellite giant, merged with it, creating Eutelsat Group. As reported by the BBC, the UK government saw strategic value in owning a stake in a global satellite network post-Brexit.

Today’s OneWeb is different. It’s not targeting individual consumers directly. Its focus is on B2B and Government: backhaul for mobile networks (4G/5G), connectivity for ships, planes, enterprise, and crucial government/military communications. It’s the quiet, infrastructure-focused backbone.

Project Kuiper: The “Apex Predator-in-Waiting”

Amazon’s Kuiper is the mystery. Announced in 2019, it is the brainchild of Jeff Bezos, who, through his separate company Blue Origin, also has a vested interest in space access. Amazon’s FCC license stipulates it must launch 50% of its planned 3,236-satellite constellation by July 2026—a massive deadline looming on the horizon.

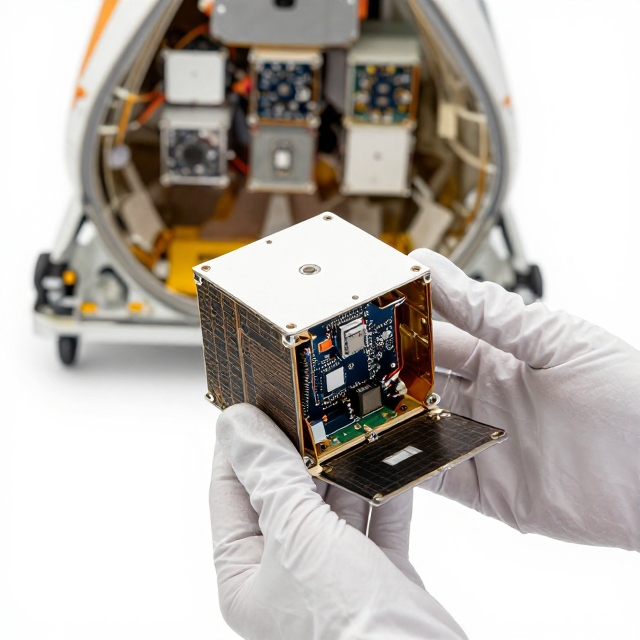

Kuiper’s advantage is Amazon’s core competencies: massive scale, supply chain mastery, and deep integration with the AWS behemoth. Imagine satellite data seamlessly flowing into AWS data centers for processing, or services bundled with Amazon Prime. Their potential for a vertically integrated ecosystem is unmatched. They’ve announced ambitious tech: compact, low-cost customer terminals (like their ultra-slim “Standard” model), and advanced optical inter-satellite links (lasers) from day one.

But as CNBC has detailed, their path has been slower. They’ve signed the largest commercial launch deal in history—buying rides on every heavy-lift rocket available (Blue Origin’s New Glenn, Vulcan, Ariane 6)—but have been waiting for those rockets to be ready. Their first two prototype satellites launched successfully in October 2023, and they claim mass production is beginning. The world is watching to see if Amazon can translate its earthly logistics genius to space.

Head-to-Head-to-Head: Breaking Down the Tech & Service

1. The Constellations: Architecture is Destiny

- Starlink: Operates in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) at ~550km. It started with a single shell but is rapidly expanding to include Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO ~340km) for lower latency and higher shells. It uses both radio and, increasingly, laser inter-satellite links. These lasers are a game-changer; they allow data to hop between satellites without going to a ground station, enabling true global coverage over oceans and poles. A NASA study acknowledged the advanced nature of this system but also raised concerns about the complexity it adds to collision avoidance.

- OneWeb: Also LEO, but flying higher at ~1,200km. This higher altitude means each satellite covers a wider area, so they need fewer satellites (~650) for global coverage. However, it comes with a trade-off: slightly higher latency. Their first-generation satellites do not have inter-satellite lasers; data must travel down to a ground station and back up. This requires a global network of “gateway” earth stations, which can be a political and logistical hurdle.

- Kuiper: Plans a three-tiered LEO architecture at 590km, 610km, and 630km. Like Starlink, its satellites are designed with optical inter-satellite links (OISLs) as standard. This indicates they are aiming for a fully networked mesh from the outset, designed for high-performance, low-latency global routing.

2. The User Experience: Dishes, Data, and Dollars

- Starlink: Offers direct-to-consumer service. You order a kit (dish, router), plug it in, and point at the sky. Speeds are typically 50-200 Mbps, with a latency of 25-50ms—good enough for gaming and video calls. Plans range from ~$120/month for residential to specialized (and more expensive) mobile plans for RVs, boats, and aircraft. Their hardware has evolved quickly, becoming lighter and more efficient.

- OneWeb: You will not buy a OneWeb dish for your home. They sell capacity to internet service providers (ISPs), telecom companies, airlines, and governments. So, your experience would be through a local ISP in a remote community, or the Wi-Fi on a cruise ship or long-haul flight. They focus on reliability and integration into existing telecom infrastructure.

- Kuiper: Amazon has previewed three customer terminals. The most talked-about is the ultra-compact “Standard” model, aiming for a price point of under $400 to produce. The goal is clear: make the hardware cheap and accessible. While pricing isn’t set, the intent to be competitive is. The deep question is how they will bundle or integrate services with Amazon Prime, AWS, or other services.

3. The Launch Race: The Road to Orbit

This is where the rubber meets the vacuum of space.

- Starlink: Has a staggering lead. With over 6,000 satellites launched as of early 2025 (per Jonathan’s Space Report), they operate more satellites than all other active satellites combined. Their reuse of Falcon 9 boosters (some flying 20+ times) makes this economically feasible.

- OneWeb: Completed its first-generation constellation of 648 satellites in March 2024. They used a mix of launch providers after the geopolitical break with Soyuz, relying heavily on SpaceX and India’s ISRO—a fascinating pivot in itself.

- Kuiper: Is the under-launched but over-resourced newcomer. Their 2026 FCC deadline is a gun to their head. They must launch nearly 1,600 satellites in about two years. Their success hinges entirely on the delayed new rockets (New Glenn, Vulcan, Ariane 6) entering reliable, regular service. It will be the most intense satellite deployment campaign in history if they pull it off.

The Challenges: It’s Not All Clear Skies

Space Junk and Congestion: LEO is getting crowded. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and other international bodies are scrambling to update rules for “megaconstellations.” Close approach alerts are routine. All operators must have robust de-orbiting plans (Starlink satellites naturally de-orbit in ~5 years from their low altitude), but the long-term sustainability of the orbital environment is a major concern for scientists and governments.

The Financial Black Hole: Building, launching, and operating a constellation costs tens of billions. Starlink only achieved cash-flow positivity in late 2023, after massive investment. OneWeb required a sovereign bailout. Kuiper is projected to cost Amazon over $10 billion. The return on investment is long-term and uncertain.

The Ground Game: Satellites are only half the system. You need user terminals, gateway stations, network operations centers, and global regulatory approval in every country you serve. This is a mammoth logistical and political task. Amazon and SpaceX have experience with global scale; this is their battleground as much as space.

The Ultimate Question: Is There Enough Demand?

The market is finite. They are competing for the estimated 5-10% of the global population that is unserved or underserved by terrestrial fiber/cable. They also compete for specialized mobility (maritime, aviation) and government contracts. There may not be room for three mega-constellations to be wildly profitable.

The Human Impact: What This Really Means for Us

Beyond the corporate rivalry, this technology is transformative.

- Closing the Digital Divide: For a school in the Alaskan tundra, a clinic in rural Africa, or a farm in Australia, this isn’t about choosing a provider; it’s about getting connected for the first time. It enables education, telemedicine, and economic participation.

- A New Layer of Global Infrastructure: Think of these networks as a new, smart “utility layer” in the sky. It will enable the Internet of Things (IoT) everywhere, from environmental sensors to smart shipping containers.

- Resilience and Redundancy: In disasters that destroy ground infrastructure, satellite networks can be restored in hours. They provide a vital backup for global communications.

- Changing How We Work and Travel: Reliable, high-speed internet on planes, ships, and in RVs is dissolving the last boundaries of the “office” and enabling new forms of travel and exploration.

The Verdict: Who Wins?

This isn’t a race with a single winner. The market is likely to be segmented, much like the automotive industry has cars, trucks, and luxury brands.

- Starlink is positioned to be the dominant retail and “prosumer” brand. Its first-mover advantage, continuous innovation, and vertical integration (its own rockets) give it a formidable moat. It will likely remain the go-to for remote homes, adventurous travelers, and early adopters.

- OneWeb (Eutelsat Group) is carving out a powerful niche as the trusted, behind-the-scenes wholesale and government provider. Its ownership structure gives it political heft in Europe, India, and allied nations. It may not be a household name, but it could become the backbone for countless other services.

- Project Kuiper is the wildcard with the highest ceiling. If it executes its launch campaign and leverages the AWS ecosystem, it could become the most integrated and potentially consumer-friendly option. Its success depends entirely on executing a historically unprecedented launch rate.

The true winner, in the end, could be us—the users. Competition will drive down costs, improve technology, and expand access. The night sky may have gained some moving dots, but the Earth below is about to become more connected, more resilient, and perhaps, a little bit smaller.

FAQ Section

Q1: What’s the main difference between Starlink, OneWeb, and Kuiper in one sentence?

A: Starlink is the fast-moving, consumer-focused pioneer; OneWeb is the government-backed B2B and infrastructure specialist; and Project Kuiper is Amazon’s yet-to-launch, ecosystem-powered challenger.

Q2: Which service is available to me right now for my home?

A: As of early 2025, only Starlink offers direct-to-consumer residential services globally. OneWeb sells capacity to internet service providers and businesses, so you might get it through a local company. Kuiper is still in testing and not yet available to the public.

Q3: Who has the most satellites in orbit?

A: Starlink has a massive lead, having launched over 6,000 operational satellites to date—more than any other company or country. OneWeb has completed its ~650-satellite first-generation constellation. Kuiper has launched only two prototypes so far. (Source: Jonathan’s Space Report)

Q4: Why are astronomers concerned about these satellite networks?

A: The sheer number of satellites, especially in low orbits, can leave bright streaks in telescope images, disrupting astronomical observations. Companies are testing mitigations like darkening coatings and sunshades. The International Astronomical Union maintains ongoing reports on the issue. (Source: IAU Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky)

Q5: What’s the big deal about “laser links” between satellites?

A: Optical Inter-Satellite Links (lasers) allow data to travel directly between satellites without bouncing down to a ground station. This dramatically reduces latency (lag) for long-distance connections and enables true global coverage over oceans and poles, making the network faster and more resilient. Both Starlink (adding them) and Kuiper (designing them in from the start) are implementing this tech.

Q6: Is satellite internet going to replace my cable or fiber?

A: Very unlikely. The primary goal of these LEO constellations is to serve the unserved and underserved—rural, remote, marine, and airborne users, where laying cable is impossible or too expensive. In cities, fiber will almost always offer higher speeds and lower costs. Think of it as complementary, not a replacement.

Q7: How does OneWeb, which went bankrupt, still exist?

A: OneWeb was rescued in 2020 by a consortium including the UK Government and Bharti Global, and later merged with the European satellite operator Eutelsat. This provided the capital and strategic partnerships needed to complete its constellation, pivoting its focus to business and government services. (Source: BBC News)

Q8: When will Amazon’s Kuiper be available, and what’s their biggest hurdle?

A: Amazon aims to launch beta testing with commercial customers in 2025. Their biggest challenge is a looming FCC deadline: they must launch and operate 1,618 of their 3,236 planned satellites by July 2026. This requires an unprecedented launch campaign, dependent on new rockets from multiple providers becoming operational.

Q9: Are these satellites creating a space junk problem?

A: It’s a major concern. While all operators have plans to de-orbit satellites at end-of-life (usually within 5 years for LEO), the sheer volume increases collision risk and tracking complexity. Regulatory bodies like the FCC have begun imposing new rules for post-mission disposal and collision avoidance. Responsible management is critical for sustainable space use. (Source: FCC Space Innovation)

Q10: Which one should I choose?

A: It depends entirely on your needs:

- For the best future integration with cloud services and e-commerce, Kuiper has intriguing potential, but you’ll have to wait and see its real-world performance.

- For a remote home, RV, or boat: Starlink is your current, proven option.

- For a business, telecom company, or government project: You would likely contract with a partner that uses OneWeb or (eventually) Kuiper capacity.