Look up at the night sky. What do you see? Points of light. Stars, planets, the occasional satellite tracing a silent path. It feels vast, yes, but also… random. A scattering of glitter on a black velvet sheet.

But what if I told you that this view is an illusion? A trick of our limited perspective, like an ant standing on a single thread of a sprawling spiderweb, seeing only the fiber beneath its feet, oblivious to the magnificent, intricate architecture it’s a part of.

The truth is far grander, more structured, and more beautiful than we ever imagined. We don’t live in a universe of scattered stars and galaxies. We live inside a Cosmic Web.

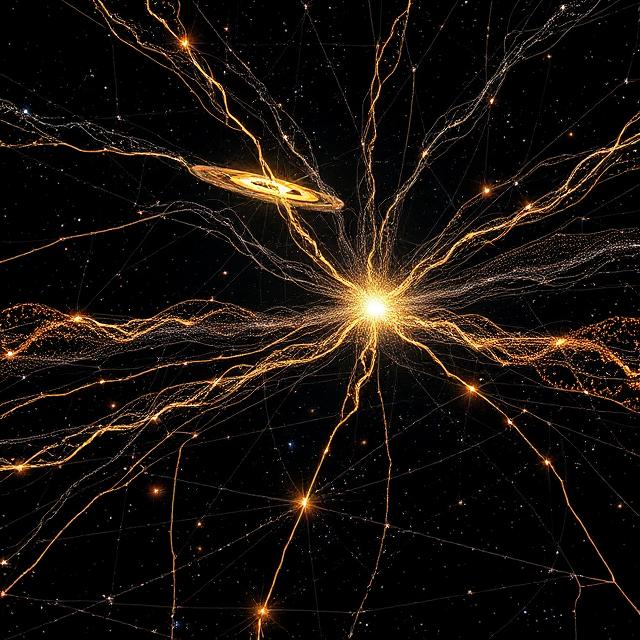

This isn’t science fiction. It’s the defining framework of our universe, the largest-scale structure we know of. It’s a colossal network of galaxies strung along invisible filaments of dark matter, stretching for billions of light-years, with immense, empty voids between them. Think of it as the universe’s skeleton, its nervous system, and its most breathtaking work of art—all rolled into one.

Forget isolated islands of stars. We are residents of a metropolis in a web that connects everything.

From Chaos to Cosmos: How We Discovered the Scaffolding of the Universe

For most of human history, our cosmic maps were blank. Then, they became messy. With powerful telescopes, we saw galaxies—spirals, elliptics, irregular blobs—and for decades, astronomers assumed they were distributed more or less evenly throughout space. The “Cosmological Principle” suggested that, on a large enough scale, the universe should look the same in every direction.

But in the 1970s and 80s, a puzzle began to emerge. Astronomers like Margaret Geller, John Huchra, and Valerie de Lapparent, conducting the groundbreaking Center for Astrophysics (CfA) Redshift Survey, began systematically mapping the distances to galaxies. Instead of a uniform scatter, their maps revealed something startling: galaxies were clumped. They formed walls, like the “Great Wall” they discovered—a vast sheet of galaxies over 500 million light-years long. They found hints of filamentary structures and, most tellingly, gigantic, empty regions where almost nothing lived: cosmic voids.

The data points weren’t chaotic. They were tracing the outline of something much larger. The term “Cosmic Web” was coined, and a new picture of the universe was born. We weren’t just cataloging individual cities; we were discovering the continents, mountain ranges, and empty oceans of the cosmos.

The Invisible Architect: Dark Matter Weaves the Web

So, what builds a web on a cosmic scale? The answer lies in the universe’s greatest mystery: dark matter.

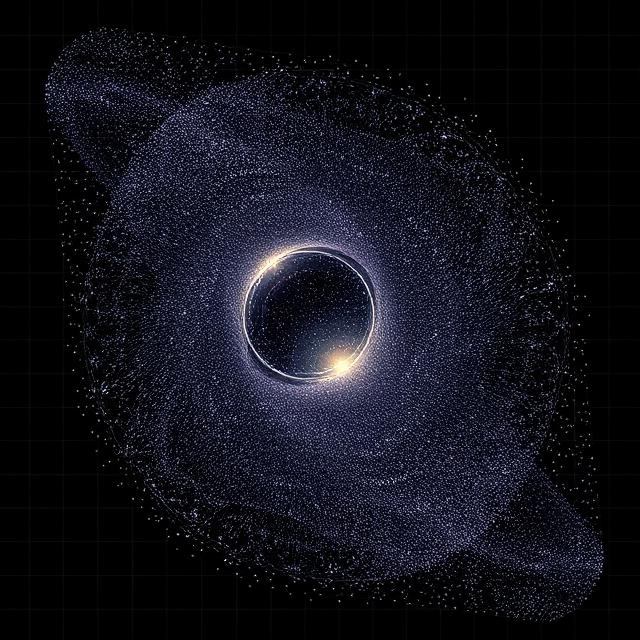

We can’t see dark matter. It doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light. But we know it’s there because of its immense gravitational pull. It makes up about 27% of the universe (ordinary matter—you, me, stars, galaxies—is a paltry 5%). In the early universe, after the Big Bang, there were tiny, random fluctuations in density. Regions with a little more dark matter had a little more gravity.

Over billions of years, gravity did its slow, relentless work. Dark matter, under its own gravity, began to collapse first, forming an immense, invisible scaffolding. It flowed into:

- Filaments: Vast, river-like strands where dark matter (and later, regular matter) is concentrated.

- Nodes: Dense knots at the intersections of filaments, where galaxy clusters—the universe’s most massive structures—would eventually form.

- Voids: The empty spaces in between, the cosmic deserts that make up most of the universe’s volume.

Imagine pouring syrup onto a pane of glass. It doesn’t spread evenly; it forms rivers and pools, with empty spaces between. Dark matter is that syrup, and gravity is the tilt of the glass. The ordinary, “baryonic” matter—the gas and dust that make stars and planets—was simply along for the ride. It flowed down into the gravitational wells created by the dark matter web, condensing into galaxies along the filaments and especially at the crowded intersections.

The stunning conclusion: Galaxies are not the main event. They are merely the illuminated signposts, the streetlights along the hidden dark matter highways of the Cosmic Web.

Mapping the Unmappable: How Do You See a Spiderweb in the Dark?

If the web is made of invisible stuff and the visible bits are scattered across billions of light-years, how do we actually map it? This is where modern cosmology becomes a feat of extraordinary ingenuity.

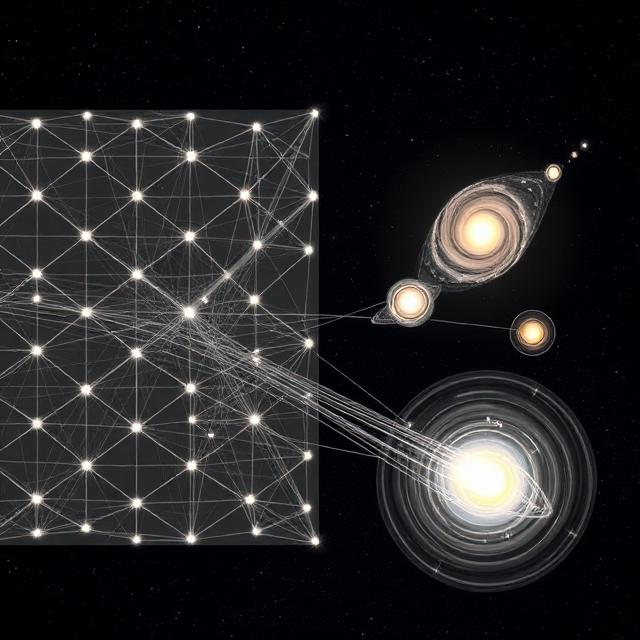

- Galaxy Surveys: The direct approach. Projects like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) have meticulously mapped the 3D positions of millions of galaxies. By using redshift (the stretching of light from receding objects) to measure distance, astronomers can plot galaxies in a vast volume of space. The resulting maps, like the famous SDSS “slice of the universe,” show the web in stunning, statistical detail—filaments, walls, and voids etched in points of light.

- Quasar Absorption Lines: Here’s a clever trick. Quasars are ultra-bright beacons from the early universe. As their light travels through space for billions of years to reach us, it passes through the diffuse gas that lies along the filaments of the web. This gas isn’t dense enough to form stars, but it’s there—the “missing” ordinary matter. It absorbs specific wavelengths of the quasar’s light. By studying the “absorption lines” in a quasar’s spectrum, astronomers can detect this tenuous, invisible gas. It’s like seeing the silhouette of the web against a brilliant backlight. Studying multiple quasars in proximity has even allowed scientists to map the “cosmic web filament” structure in 3D.

- Computer Simulations: We can’t run the universe in a lab, but we can in a supercomputer. Simulations like IllustrisTNG and Millennium start with the conditions of the early universe and the laws of physics (gravity, hydrodynamics, etc.). They then simulate the evolution of billions of particles of dark and ordinary matter over 13.8 billion years. The result? Virtual universes that spontaneously form a cosmic web are uncannily similar to the one we observe. These simulations are our testing ground, letting us run experiments on how galaxies form and evolve within the web’s architecture.

- The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB): This is the afterglow of the Big Bang, a baby picture of the universe. Tiny temperature fluctuations in the CMB are the seeds of all future structure. By studying the pattern of these fluctuations, cosmologists can predict what the web should look like. The match between these predictions and our actual maps of galaxies is one of the strongest pieces of evidence we have for our entire model of cosmology, including dark matter and dark energy.

Our Address on the Web: Where Does the Milky Way Live?

Let’s get local. Where are we in this unimaginably large structure?

Our home galaxy, the Milky Way, is not in a particularly special place—and that’s what makes it so fascinatingly typical. We reside in a galaxy group called the Local Group (which includes Andromeda and about 50 other smaller galaxies). This group is located on the outskirts of a much larger structure: the Laniakea Supercluster.

Laniakea, meaning “Immense Heaven” in Hawaiian, is a web-like supercluster comprising over 100,000 galaxies. It’s not a dense blob, but a sprawling network of filaments. We are on a spur of one of these filaments, flowing gravitationally toward the supercluster’s dense core, the Virgo Cluster.

But on the other side? There is a void. The Local Void is a vast, empty region of space bordering our part of the filament. We are, quite literally, on the shoreline of a cosmic ocean of nothingness. Our galaxy, and all the stars within it, exists in the delicate balance between the pull of the dense web and the emptiness of the void.

The Web’s Influence: It’s Not Just Background Decoration

The Cosmic Web isn’t a passive stage; it’s an active player in the life of galaxies. Living in this interconnected environment has profound consequences:

- Galaxy Nourishment: Filaments act as “cold gas streams.” They funnel fresh, pristine hydrogen gas from the voids into the galaxies along their lengths, providing the fuel for new star formation. A galaxy’s position in the web dictates its diet.

- Galactic Metropolis vs. Countryside: A galaxy living in a dense cluster (a node) has a violent, social life. It experiences frequent interactions and mergers with other galaxies. Its surrounding gas is often stripped away by the hot intracluster medium, starving it of fuel and leading to a population of old, “red and dead” elliptical galaxies. A galaxy in a quiet filament or alone in a void is more isolated. It can evolve slowly, spinning peacefully and forming stars at a steadier rate, often becoming a spiral like our Milky Way.

- The Void Dwellers: The galaxies that do form in voids are fascinating outliers. They tend to be smaller, less evolved, and often irregular in shape. Isolated from the dense flows of the web, they are cosmic backcountry towns, developing in their own unique ways.

The Unanswered Questions: Where the Mystery Deepens

For all we’ve learned, the Cosmic Web is still shrouded in mystery. Each answer opens new, thrilling questions:

- What is Dark Matter? This is the trillion-dollar question. We see its gravitational shadow in the web’s structure, but we have no idea what particle (or phenomenon) it actually is. Directly detecting it would revolutionize physics.

- How Does Baryonic Matter Really Behave? The interplay between gas, magnetic fields, and supermassive black holes within the web is intensely complex. How exactly does gas cool, heat, and flow into galaxies? Our simulations are good, but they’re still approximations.

- What Role Does Dark Energy Play? The mysterious force accelerating the universe’s expansion is the ultimate fate-weaver. As dark energy pushes the universe apart, it may be stretching the filaments of the web, altering the flow of gas, and eventually isolating galaxy clusters as “island universes” in a far, far distant future.

A Tapestry of Connection: Why the Cosmic Web Matters to Us

This might all seem like abstract, distant science. But understanding the Cosmic Web does something profound: it changes our story.

For millennia, our cosmologies have reflected our societies. We saw gods, then celestial spheres, then clockwork mechanics. The 20th century gave us the lonely, expanding universe—a great, empty void.

The 21st century gives us a new metaphor: the network.

We are not lonely dots in a dark emptiness. We are nodes in a network of unimaginable scale and beauty. The same forces that sculpted the web—gravity, the fundamental laws of physics—operate within us. The calcium in our bones, the iron in our blood, was forged in stars that formed because of the gentle tug of dark matter in a filament of the web billions of years ago.

We are not just in the universe; the universe is in us, and we are woven into its grandest structure.

The next time you look up at that seemingly random night sky, remember: you are gazing out from within a single thread of the greatest tapestry in existence. You are a part of the Cosmic Web, and it is a part of you. And the most exciting chapters in understanding our place within it are being written right now, by curious humans pointing telescopes and running simulations, forever striving to map the contours of our true home.

FAQ Section

Q1: What is the Cosmic Web in simple terms?

A: Think of the universe not as a random scatter of galaxies, but as a giant, three-dimensional spiderweb. The “threads” of this web are long filaments made of invisible dark matter and gas, dotted with galaxies. Where threads cross, you get dense knots (galaxy clusters). The huge empty spaces between the threads are called cosmic voids. It’s the largest structure we know of.

Q2: How is the Cosmic Web different from just a bunch of galaxies?

A: Galaxies are the result of the Cosmic Web, not the cause. The web’s structure is primarily built by dark matter’s gravity. Galaxies form within this pre-existing dark matter skeleton, like dew forming on a spiderweb. The web defines the universe’s large-scale organization, showing how everything is interconnected over billions of light-years.

Q3: If dark matter is invisible, how do we know it builds the web?

A: We see its gravitational effects. The distribution of visible galaxies maps a pattern that could only be held together by far more mass than we can see—that’s the dark matter scaffolding. Supercomputer simulations that start with dark matter and the laws of gravity successfully recreate a web structure that looks exactly like the one we observe with our telescopes.

Q4: Where is our Milky Way galaxy located in the Cosmic Web?

A: We’re not in a special downtown area! We live in a quieter suburb. The Milky Way is part of the Local Group of galaxies, which sits on a filament on the outer edges of the Laniakea Supercluster. We’re also right next to a huge, mostly empty region called the Local Void. So, we’re on a cosmic shoreline between structure and emptiness.

Q5: What are cosmic voids, and are they empty?

A: Voids are the vast “empty” spaces between the filaments of the web, making up most of the universe’s volume. They aren’t empty—they contain very, very diffuse gas and a few isolated, “lonely” galaxies. But compared to the dense filaments and clusters, they are the universe’s great deserts.

Q6: How do scientists actually map something so immense?

A: Using multiple clever techniques:

- Galaxy Surveys: Projects like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey plot the 3D locations of millions of galaxies, revealing the web’s pattern statistically.

- Quasar Backlighting: Using brilliant distant quasars as flashlights to detect the faint gas in filaments by its shadow.

- Supercomputer Simulations: Running the universe’s evolution from the Big Bang to today to see how the web forms in theory.

Q7: Does the Cosmic Web affect our galaxy?

A: Absolutely. It shaped our past and influences our present. The filament our Milky Way resides in likely funneled gas that helped build our galaxy and form stars. Our galaxy’s relatively calm spiral shape and ongoing star formation are also influenced by our specific, less-crowded location in the web.

Q8: What’s the biggest unanswered question about the Cosmic Web?

A: The nature of dark matter itself remains the top mystery. We see its shadow in the web’s architecture, but we don’t know what it’s made of. Furthermore, understanding the detailed physics of how ordinary gas flows, cools, and forms stars within this dark matter framework is an active and thrilling frontier of research.

Conclusion: Our Place in the Tapestry

We began by looking up at a night sky that seemed random—a scatter of stars against an endless black. We end by seeing that same sky for what it truly is: a single, intricate thread in the largest and most beautiful structure known to exist.

The Cosmic Web is more than a scientific model; it is a fundamental revision of our cosmic address. We are not isolated passengers on a lonely rock in a meaningless void. We are active participants in a dynamic, evolving network of staggering scale and elegance. The iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones, and the very planet we call home are products of this web—forged in stars that themselves were born from gas flowing along dark matter filaments billions of years ago.

This understanding bridges the vast and the intimate. The same gravity that holds you to the Earth sculpted the continents of galaxies. The same natural laws running through your veins orchestrate the slow dance of superclusters. In learning to map the web, we are not just charting distant points of light; we are learning the deep history of our own origins and the architectural blueprint of reality itself.

Yet, for all we’ve mapped, the web remains humbling. The true nature of the dark matter that knits it together is still a mystery. The detailed story of how galaxies are born, fed, and die within their strands is still being written. The influence of dark energy, silently stretching the filaments of the future, is a cliffhanger in our cosmic narrative.

And that is perhaps the most humanizing lesson of all. The quest to understand the Cosmic Web is a testament to our curiosity—our innate drive to look into the darkness and not only see patterns, but to seek our connection to them. It is a story still unfolding, with every new telescope, every complex simulation, and every dedicated scientist adding another stitch to our map of understanding.

So, the next time you step outside on a clear night, take a moment. Look past the singular stars. Imagine the invisible architecture—the grand filaments, the bustling clusters, the profound voids—all part of a single, magnificent web. You are not just looking at the universe. You are looking out from within its living, breathing structure. You are, and always have been, a conscious part of the Cosmic Web. And in knowing that, the universe becomes not a cold space, but a home of breathtaking connection.