Imagine you’re trying to listen to a beautiful, complex symphony being played in a thunderstorm. The music is there—the soaring violins, the powerful brass—but it’s constantly being drowned out by cracks of thunder and the roar of rain. You catch fleeting, glorious moments, but the overall piece is lost in the chaos.

This, in essence, is the grand challenge of quantum computing today. We are in the NISQ era—the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum era. We have the instruments; we’ve built quantum processors with 50, 100, even 400+ qubits. They can perform calculations that would stump any classical supercomputer for specific, highly complex problems. This is the symphony. But the noise—the thunderstorm of environmental interference, hardware imperfections, and quantum decoherence—threatens to drown it all out before we can hear the final, transformative chord.

This is where the unsung hero of the quantum world enters: Quantum Error Correction (QEC). But in the NISQ era, we can’t just deploy the full, perfect version of QEC we’ve theorized about. We have to be clever, pragmatic, and resourceful. We have to use NISQ-era error correction and mitigation techniques.

This blog post is your guide through this noisy landscape. We’ll demystify why quantum bits are so fragile, explore the dream of full fault-tolerant quantum computing, and then dive deep into the ingenious, stopgap solutions that are allowing us to squeeze valuable results from our imperfect quantum machines right now.

Why are Qubits So… Delicate? The Roots of Quantum Noise

To understand the solution, we must first appreciate the problem. Classical bits in your laptop or phone are robust. They are either a 0 or a 1, represented by a stable, macroscopic physical property (like a voltage). A bit flip (a 0 becoming a 1) is possible, but relatively rare and easy to guard against with simple redundancy.

Qubits are a different beast entirely. Their power comes from superposition (being in a combination of 0 and 1) and entanglement (a deep, “spooky” connection between qubits). But this power comes at the cost of extreme fragility.

The main sources of noise that plague qubits are:

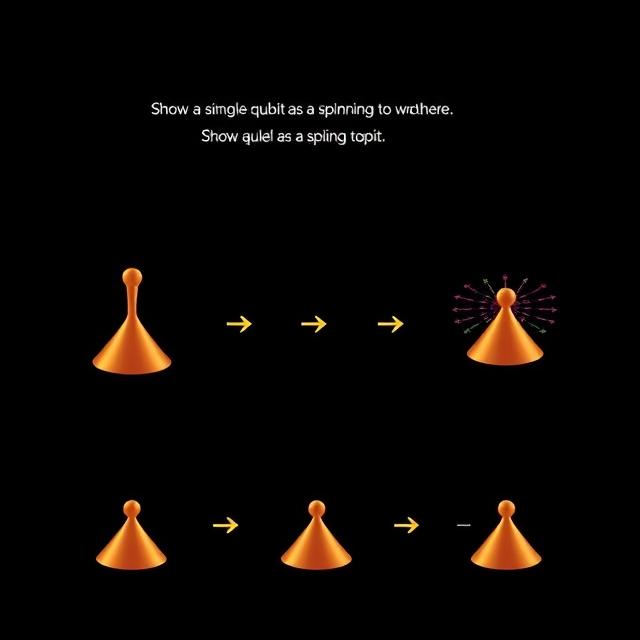

- Decoherence: This is the ultimate enemy. A qubit in superposition is like a spinning top. Left alone, it will eventually wobble and fall. Decoherence is the process where the qubit’s delicate quantum state interacts with its environment—stray electromagnetic fields, vibrations, heat—and “collapses” into a boring, classical 0 or 1. The time a qubit can maintain its coherence is critically short, limiting the length of computations we can run.

- Gate Errors: The operations we perform on qubits (quantum gates) are imperfect. A rotation might be a fraction of a degree off. A two-qubit entangling gate might not be perfectly calibrated. These tiny errors accumulate rapidly throughout a calculation.

- Readout Errors: Finally, when we measure a qubit to read out the result, we might get it wrong. The qubit might be in state |1>, but our measurement apparatus incorrectly reports it as a |0>.

These errors aren’t just occasional glitches; they are a constant, pervasive reality in today’s quantum hardware. Without a strategy to combat them, any meaningful quantum computation is impossible.

The Promised Land: Full Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation

Before we talk about the NISQ-era workarounds, let’s look at the ultimate goal: Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation (FTQC).

The classical world solved its error problem with brilliant simplicity. If a single bit is unreliable, use three. Store the information not as 0 or 1, but as 000 or 111. If one bit flips, a majority vote (two out of three) can correct the error. This is the concept of redundancy.

We can’t just copy a qubit. The No-Cloning Theorem is a fundamental law of quantum mechanics that states it’s impossible to create an identical copy of an arbitrary unknown quantum state. So, we have to be much smarter.

The breakthrough, pioneered by theorists like Peter Shor and others, was Quantum Error Correction (QEC) Codes. These are clever ways to encode the information of one “logical” qubit into the entangled state of multiple “physical” qubits.

The most famous and foundational example is the Surface Code.

A Simple Analogy for the Surface Code

Imagine the logical qubit’s information isn’t stored in a single point, but spread out across a checkerboard. Each square on the board is a physical qubit. We don’t measure the individual qubits directly (that would collapse the state). Instead, we measure the relationships between them—specifically, whether the colors (quantum states) of adjacent squares are the same or different.

- We place a special “measurement qubit” in the center of every four “data qubits.”

- These measurement qubits perform constant, non-destructive checks on their four neighbors, asking a simple parity question: “Are you all the same, or is there a mismatch?”

- A change in the output of these parity checks signals that an error has occurred somewhere on the board. By analyzing the pattern of these changes across the entire lattice—like connecting the dots—we can pinpoint the exact location and type of the error (a bit-flip or a phase-flip) without ever knowing the underlying information of the data qubits themselves.

This is the magic of QEC: detecting and correcting errors without collapsing the quantum state.

The surface code is remarkably resilient and has a high threshold. This is the maximum error rate per physical qubit that the code can tolerate. If your hardware is better than this threshold (say, 1 error per 1,000 operations), then by scaling up the checkerboard (using more and more physical qubits), you can make the logical qubit arbitrarily stable. The errors on the physical qubits are constantly being corrected faster than they can corrupt the logical information.

This is the dream. But here’s the catch: current estimates suggest you might need 1,000 to 10,000 physical qubits to create a single, highly reliable logical qubit with the surface code. We simply don’t have that scale of high-quality qubits yet. We are in the NISQ era.

Welcome to the NISQ Era: Where We Are Today

The term “NISQ” was coined by the renowned physicist John Preskill. It describes our current technological plateau:

- Noisy: Our qubits are error-prone, with coherence times and gate fidelities that are good, but not good enough for FTQC.

- Intermediate-Scale: We have processors with tens to hundreds of qubits—enough to perform tasks beyond classical simulation for certain problems, but not enough to implement full-scale QEC.

So, are we stuck, just waiting for better hardware? Absolutely not. This is where the field gets creative.

NISQ-Era Error Mitigation: Doing More With Less

Since we can’t yet build the massive redundancy required for FTQC, researchers have developed a suite of clever techniques known as Error Mitigation. The goal here is not to correct errors in real-time, but to characterize the noise and then post-process our results to statistically subtract its effects. It’s like recording the symphony in the thunderstorm many, many times, and then using software to average out the random noise, hoping to reveal the underlying music.

Let’s explore the key techniques powering NISQ algorithms today.

1. Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE)

The core idea of ZNE is elegant in its simplicity: if you can’t remove the noise, amplify it to understand it.

- Intentionally Amplify Noise: A quantum circuit is run, but before execution, we deliberately stretch the duration of the gates or add extra identity operations. This effectively makes the computation “take longer,” allowing more noise to accumulate. We run the same circuit at different “noise levels” (e.g., 1x, 1.5x, 2x the original noise).

- Collect Noisy Results: For each noise level, we run the circuit many times (shots) and collect the results. The output becomes progressively more corrupted as the noise increases.

- Extrapolate to Zero: We then plot the results against the noise level and extrapolate the curve back to what the result would have been at a “zero-noise” level.

It’s a statistical best guess, but for many practical problems, it provides a dramatic improvement in the accuracy of the final result.

2. Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC)

This technique is more advanced. It treats the noise in a quantum computer as a known, undesirable “channel” that acts on our ideal quantum state.

- Characterize the Noise: First, we run extensive benchmarking tests on the hardware to build a precise model of its noise profile. We learn exactly what errors are most likely to occur and when.

- Create an “Inverse” Noise Model: Using this knowledge, we mathematically construct a set of operations that represent the inverse of the noise.

- Apply the Inverse Probabilistically: We can’t apply this inverse directly (it’s not a physical quantum operation), but we can simulate its effect. We run the original circuit many times, but randomly, in a small percentage of runs, we insert specific “compensating” gates into the circuit. When we aggregate all the results, the average output is a much closer approximation to the noiseless result.

Think of it as adding a specific “antidote” operation for every possible “poison” (error) the hardware can introduce, applied in a carefully controlled, statistical manner.

3. Dynamical Decoupling (DD)

This is a simpler, yet highly effective, “shielding” technique. Imagine you have a qubit that’s sitting idle, waiting for its turn in a computation. During this time, it’s most vulnerable to decoherence from its environment.

Dynamical Decoupling involves applying a rapid sequence of simple, fast pulses (like X and Y gates) to the idle qubit. These pulses effectively “refocus” the qubit, like spinning it around so that the slow, drifting effects of environmental noise cancel themselves out. It’s a way of keeping the qubit “awake” and protected without actually performing a computation. It’s a remarkably low-overhead way to extend the effective coherence time of qubits.

The Bridge: Small-Scale QEC Codes on NISQ Devices

While full FTQC is out of reach, researchers are actively running small-scale QEC experiments on NISQ devices. These are crucial proof-of-concept demonstrations.

You won’t see a 1000-qubit surface code yet, but you might see a 3-qubit bit-flip code or a 5-qubit code (the smallest code that can correct for an arbitrary error on a single qubit). These experiments are not about creating a stable logical qubit for a long computation. Their goal is to demonstrate that the fundamental principle works.

They show that when they introduce a known error into the system, the syndrome measurements (the parity checks) can detect it, and a correction can be applied. Success is measured by a small but statistically significant increase in the final fidelity of the logical state compared to an unencoded qubit.

These experiments are the training wheels for the quantum computing industry. They are how we test our control systems, improve our gate fidelities, and build the foundational knowledge required to scale up.

The Real-World Impact: Why This Matters Now

You might be thinking, “This is all academic until we have fault-tolerance.” But that’s not true. NISQ-era error mitigation is already having a tangible impact on the development of useful quantum algorithms.

- Quantum Chemistry: Simulating molecules for drug discovery or materials science requires high precision. Techniques like VQE (Variational Quantum Eigensolver) paired with ZNE or PEC are being used to calculate molecular energies with an accuracy that was previously impossible on noisy devices.

- Optimization: For complex logistics and scheduling problems, QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm) relies on error mitigation to produce viable solutions that are better than random guessing.

- Machine Learning: Quantum machine learning models are extremely sensitive to noise. Error mitigation is essential for training these models effectively on today’s hardware.

These techniques are the reason we can run meaningful, albeit small-scale, experiments that provide a glimpse into the future utility of quantum computers.

The Road Ahead: From NISQ to FTQC

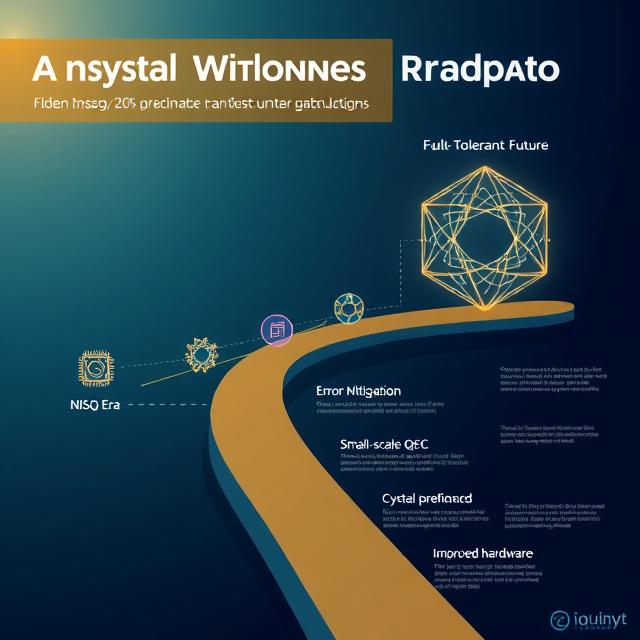

The journey from the noisy present to the fault-tolerant future is a continuous one, not a single leap. It looks something like this:

- NISQ (Today): Reliance on error mitigation and small-scale QEC demonstrations. Useful for specific, “noise-resilient” problems and for benchmarking and hardware development.

- Early Fault-Tolerance: As qubit counts grow into the thousands and quality improves, we will see the first truly scalable QEC codes implemented, perhaps with a small number of logical qubits. This will allow for significantly longer algorithms.

- Full FTQC (The Future): With millions of high-quality physical qubits, we will have a fully fault-tolerant quantum computer capable of running Shor’s algorithm for factoring large numbers, simulating complex quantum systems with absolute precision, and solving problems we can’t even conceive of today.

The development of better hardware—qubits with longer coherence times and higher gate fidelities—goes hand-in-hand with the software and theoretical advances in error correction. Each improvement in hardware raises the effectiveness of our error mitigation techniques and lowers the resource overhead required for full QEC.

FAQ: Unraveling NISQ-Era Error Correction

1. What’s the single biggest difference between full Quantum Error Correction (QEC) and NISQ-era Error Mitigation?

The biggest difference is the goal and method.

- Full QEC aims to actively correct errors in real-time as they happen. It uses many physical qubits to create a single, highly stable “logical qubit” that is protected for the entire duration of a computation. It’s like building a storm-proof concert hall for the symphony.

- NISQ-Era Error Mitigation aims to characterize the noise and statistically subtract its effects after the computation. It uses software tricks and multiple runs on the same noisy hardware to estimate what the result would have been without noise. It’s like recording the symphony in a storm many times and using software to filter out the thunder in post-production.

2. If we have these error mitigation techniques, why do we still need to build a fault-tolerant quantum computer?

Error mitigation is a powerful tool, but it has fundamental limits. Techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation become less effective as circuits get longer and more complex—the noise grows too large to extrapolate accurately. Furthermore, these methods require an exponentially increasing number of circuit runs to get a precise result, making them impractical for the massive algorithms (like Shor’s algorithm for breaking encryption) that promise quantum computing’s ultimate potential. Full fault-tolerance is the only path to running those long, complex calculations reliably.

3. What is a “logical qubit” and why do we need so many physical qubits to make one?

A logical qubit is the idealized, error-corrected version of a qubit that we want to use in our computations. It’s not a physical object but rather the information of a single qubit encoded into the entangled state of many physical qubits (the actual hardware). We need so many physical qubits (potentially 1,000+) for two reasons: first, for redundancy to spread out the information, and second, for the extra “syndrome” qubits needed to constantly measure and detect errors without collapsing the main data.

4. Are any of these NISQ error mitigation techniques used in commercial quantum computing today?

Yes, absolutely. If you use a cloud-based quantum computer from providers like IBM, Google, or Rigetti, error mitigation is often applied behind the scenes or is available as an option for users. For instance, when running a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for chemistry simulations, using Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) is a standard practice to get more accurate energy readings. These techniques are now a core part of the software stack for extracting meaningful results from current hardware.

5. I keep hearing about the “Surface Code.” Is it the only quantum error correction code?

No, the Surface Code is not the only one, but it is currently the most promising and widely researched for future fault-tolerant quantum computers. Its major advantages are a relatively high error threshold (it can tolerate noisier qubits), and its physical layout is well-suited for 2D chip architectures. However, other codes exist, like the Color Code and Toric Code, each with different trade-offs. For small-scale NISQ demonstrations, simpler codes like the 3-qubit or 5-qubit code are used because they are less resource-intensive.

Conclusion: Embracing the Noise

The story of NISQ-era quantum error correction is a story of human ingenuity. Faced with the fundamental fragility of the most powerful computers ever conceived, we haven’t given up. We’ve gotten creative.

We are learning to listen to the quantum symphony not by waiting for the storm to pass, but by building better microphones and developing sophisticated software filters. The techniques of Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Probabilistic Error Cancellation, and Dynamical Decoupling are not just stopgaps; they are the foundational tools that are teaching us how to build and control quantum systems.

They are the bridge between the tantalizing theoretical promise of quantum computing and its eventual, world-changing reality. So, the next time you hear about a breakthrough in quantum chemistry or optimization on a quantum computer, remember the silent, crucial work happening in the background—the relentless, brilliant fight against the noise.

The NISQ era is not a waiting room; it’s a vibrant workshop where the future of computation is being built, one error-corrected qubit at a time.