Imagine you’re on a cross-country road trip. Your car is reliable, the scenery is breathtaking, but about halfway through Nebraska, your fuel gauge dips perilously close to “E.” No problem, you think. You’ll just pull over at the next gas station. Now, picture that same scenario, but your “car” is a $500 million satellite, and “Nebraska” is a lonely orbit 22,000 miles above Earth. Until recently, running out of fuel meant the end of the mission—a graceful (or not-so-graceful) retirement into a graveyard orbit. But what if satellites could refuel? What if we could build gas stations in space?

This isn’t science fiction. It’s the thrilling, cutting-edge reality of orbital robotics for refueling—a technological revolution quietly unfolding above our heads. It promises to transform space from a disposable frontier into a sustainable, serviceable domain. Let’s dive into how robotic arms, smart software, and pioneering missions are building the infrastructure for a new era in space exploration.

The Problem: A Sky Full of “Almost-New” Satellites

First, let’s understand the “why.” Building and launching a satellite is a monumental feat of engineering and investment. These marvels are designed to last for years, often 10-15, with robust hardware and redundant systems. Yet, their operational life is almost always cut short by one singular, mundane limitation: they run out of propellant.

Propellant isn’t just for big moves. It’s for the small, constant adjustments—station-keeping to maintain an exact orbital slot, collision avoidance to dodge space debris, and eventually, a controlled deorbit. When the fuel tank hits empty, a perfectly functional satellite, with its powerful antennas, advanced sensors, and computers, becomes expensive, high-altitude scrap metal.

The economic and environmental absurdity is clear. We’re discarding billion-dollar assets over an empty gas tank. Furthermore, these dead satellites contribute to the growing problem of space debris, cluttering valuable orbital pathways. The solution? Don’t discard. Refuel, repair, upgrade, and extend.

The Hero: Robotic Servicing Vehicles (RSVs)

Enter the robotic mechanic. Orbital robotics for refueling centers on a specialized class of spacecraft called Robotic Servicing Vehicles (RSVs) or Mission Extension Vehicles (MEVs). These are essentially agile, intelligent space tugs equipped with advanced robotics, vision systems, and—crucially—a fresh supply of propellant.

Their mission is to rendezvous with a “client” satellite, dock with it, and either take over its attitude control (flying it like a piggyback) or directly transfer fuel to its tanks. The technical challenges here are immense, which is where robotics shines.

The Robotic Toolkit: More Than Just an Arm

- Advanced Vision Systems: Satellites weren’t built with docking ports in mind. A servicing robot must use sophisticated 2D and 3D cameras, coupled with machine vision algorithms, to identify and navigate to specific features like launch vehicle adapter rings or nozzle edges. It’s like recognizing a specific car model by its tailpipe from miles away, in blinding sunlight and pitch darkness.

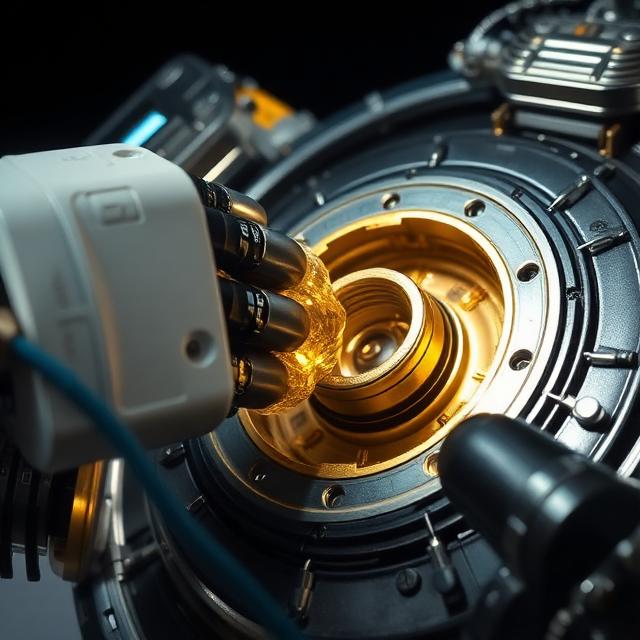

- Precision Robotic Arms: These are not the clunky industrial arms of old. They are hyper-dexterous, force-feedback manipulators capable of sub-millimeter precision. Their job might be to grapple a satellite, to deploy specialized tools, or to connect a fuel transfer line. Companies like Northrop Grumman (with their Mission Extension Vehicle) and NASA (through its OSAM-1 mission) have pioneered this technology.

- Specialized End-Effectors & Tools: This is the “wrench” in the robotic toolkit. Since satellites aren’t standardized, robots carry multi-tool interfaces. The most revolutionary tool is the Rocket Propellant Transfer (RPT) connector. For refueling, the robot must somehow access the satellite’s fuel valve, which is often hidden behind layers of insulation or never intended to be accessed in space. This might involve cutting away thermal blanket material with robotic shears before attaching the fuel line—a delicate orbital surgery.

- Autonomous Rendezvous and Docking (AR&D) Software: The final approach cannot rely on Earth-based control due to signal lag. The vehicle must autonomously make safe, gentle contact. This software is the brain of the operation, processing sensor data in real-time to make split-second decisions.

How It Works: A Step-by-Step Orbital Pit Stop

Let’s walk through a hypothetical refueling mission:

- Launch & Orbit Matching: The RSV launches and maneuvers into an orbit similar to its target client—often a telecommunications satellite in Geostationary Orbit (GEO), the most valuable and crowded orbital real estate.

- The Slow Dance of Rendezvous: Over days or weeks, the RSV performs a series of precise maneuvers to close in on the client. It uses its vision systems to identify the satellite from a distance, beginning a careful approach.

- Inspection Fly-around: Before any contact, the RSV conducts a close-proximity fly-around, capturing high-resolution imagery to confirm the client’s condition and identify the exact refueling access point.

- The Grapple: Using its robotic arm, the RSV gently grasps a predefined grapple feature on the client satellite. This is a moment of incredible tension—too fast, and you could send both spacecraft tumbling.

- Preparing the Port: If the fuel valve is covered, the robot uses its onboard tools to perform “thermal blanket cutting” or remove a cap. This is a landmark achievement in in-space assembly and manufacturing (ISAM).

- The Fluid Transfer: The robot connects its RPT hose to the client’s valve. In the microgravity of space, transferring liquid propellant (like xenon or hydrazine) is tricky. Techniques might use pressure differentials or specialized pumps to move the fluid without creating dangerous bubbles or leaks.

- Disconnect and Depart: Once the transfer is complete, the robot disconnects, secures the cap, and releases its grapple. The client satellite, now with years of new life, resumes its station-keeping duties. The RSV can either depart to service another client or remain attached as a permanent “jet pack.”

Real-World Pioneers: The Missions Making It Happen

This isn’t theoretical. Several missions are proving the concept:

- Northrop Grumman’s Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV): This has been the trailblazer. MEV-1 successfully docked with the Intelsat 901 satellite in 2020—the first commercial docking in GEO. It didn’t refuel but attached itself to provide attitude and orbit control, extending the satellite’s life by years. MEV-2 performed a similar service for Intelsat 10-02. These missions proved the core robotics of safe rendezvous and docking.

- NASA’s OSAM-1 (On-orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing 1): This is the refueling flagship. Scheduled for launch, OSAM-1’s goal is to rendezvous with and refuel Landsat 7, a government-owned Earth observation satellite that was never designed to be refueled. It will robotically cut away insulation, access the fuel valve, and transfer propellant. This mission is a critical test of the full robotic refueling toolkit.

- DARPA’s RSGS Program: The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites program aims to develop a government-owned robotic servicer that can perform multiple tasks, from inspection to repair, for both commercial and military satellites.

- Startups Entering the Fray: Companies like Astroscale are focusing on related life-extension and active debris removal services, using similar robotic grappling technologies to capture defunct satellites and clear orbital pathways.

The Ripple Effect: Benefits Beyond the Tank

The implications of successful, commonplace orbital refueling are profound:

- Economic Sustainability: Satellite operators can protect their massive investments. A refueling mission might cost $50-$100 million, but that’s a fraction of the $300+ million to build and launch a replacement. This new business model of in-orbit servicing creates a whole new industry.

- Tackling Space Debris: Refueling is the first step. The same robotic technology can be used for active debris removal—grappling defunct satellites and deorbiting them safely. It can also move “zombie” satellites to proper graveyard orbits, clearing valuable slots.

- Enabling Bold New Missions: Imagine deep-space telescopes that could be serviced and upgraded like Hubble, but at Earth-Sun Lagrange points. Or lunar Gateway stations being assembled and refueled in cis-lunar space. Refueling depots could change spacecraft design—they could be launched “dry” (without fuel), making them lighter and cheaper to launch, then filled from an orbital depot. This is a keystone for a sustainable lunar economy and future Mars missions.

- Resilience and Security: The ability to inspect, repair, or relocate satellites in orbit adds a layer of resilience to our critical space-based infrastructure (GPS, communications, weather monitoring). It also opens new avenues for national security operations.

The Challenges Ahead: The Hard Parts Aren’t All Technical

While robotics is advancing rapidly, significant hurdles remain:

- Standardization: The dream is a universal fuel port—a “gas tank lid” for satellites. The aerospace industry is slowly moving towards standards (like NASA’s RPT connector design), but convincing all satellite manufacturers to adopt them for future models is a diplomatic and commercial challenge.

- Regulation and “Rules of the Road”: Who governs these close-proximity operations? How do we prevent conflicts or ensure a servicer from one nation doesn’t approach another’s satellite without consent? The Outer Space Treaty provides a framework, but new norms and transparency measures are needed.

- Business Model Maturation: The first customers are pioneering. For the market to explode, servicing needs to be seen as a reliable, cost-effective insurance policy. Insurers will play a key role in this evolution.

- The Legacy Fleet: Thousands of satellites already in orbit weren’t designed for this. While missions like OSAM-1 are tackling this problem head-on, servicing them will always be a complex, custom job.

The Future: Orbital Infrastructure Takes Shape

Looking forward, we can see the outline of a bustling orbital ecosystem taking shape:

- The Servicing Tug Era (Now – 2030): We are here. Single-purpose RSVs extend the life of high-value GEO satellites through docking or basic refueling.

- The Depot Era (2030s): The next leap is the orbital fuel depot—a dedicated storage tank in a stable orbit. Smaller, cheaper “taxi” tugs could ferry fuel from depots to clients. This requires breakthroughs in long-term cryogenic fuel storage (like liquid hydrogen or methane) for deeper space missions.

- The Assembly & Manufacturing Era (2040s+): Robotics will move beyond refueling to assembling large structures (like giant space telescopes or solar power stations) in orbit, using materials launched from Earth or, eventually, sourced from the Moon or asteroids. Refueling will be the essential utility that makes this construction yard possible.

Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift in Our Relationship with Space

Orbital robotics for refueling represents more than a neat technical trick. It signifies a fundamental shift in how humanity operates in space. We are moving from an era of disposable, one-off missions to one of sustainability, infrastructure, and permanence.

It turns the void of space into a place of possibility—a domain where assets are maintained, upgraded, and repurposed. The robotic arms and smart vehicles we’re deploying today are the foundational tools building that future. They are the tow trucks, the service engineers, and, yes, the gas station attendants of the final frontier. And as this new ecosystem grows above us, it will unlock deeper, longer, and more ambitious journeys than we’ve ever dreamed possible. The road to the stars, it turns out, needs a few well-placed pit stops.

FAQ: Orbital Refueling Robotics

Q: Is orbital refueling currently happening?

A: Yes, in its initial stages. While direct propellant transfer is still in demonstration (see NASA’s upcoming OSAM-1 mission), life-extension via docking is operational. Northrop Grumman’s MEV vehicles are actively extending satellite lives by providing attitude and orbit control.

Q: What fuel do satellites use?

A: It varies. Many use hydrazine (a monopropellant) for simple thrusters. More advanced satellites and deep-space probes use xenon for electric ion thrusters or liquid bi-propellants (like nitrogen tetroxide and hydrazine mixtures). Future depots may store cryogenic fuels like liquid oxygen and methane for Moon and Mars missions.

Q: How does refueling help with space junk?

A: The same robotic grappling technology used for refueling is directly applicable for active debris removal. A servicer can capture a defunct satellite and either push it to a lower orbit to burn up or to a designated “graveyard” orbit, cleaning up valuable space.

Q: Aren’t these robots a security risk? Could they be used as weapons?

A: This is a serious concern and a topic of international discussion. The technology is dual-use. The key is establishing norms, transparency, and confidence-building measures. Many advocate for “rules of the road” that require pre-notification and consent before any close-proximity operation near another nation’s satellite.

Q: When will my company’s satellite be able to get a refill?

A: For newly built satellites, the timeline is accelerating. If your satellite incorporates a standard refueling port (now being designed), it could likely be serviced within the next 5-10 years as commercial servicing offerings mature. For legacy satellites without ports, the service is more complex, custom, and likely further out.

For further reading on the broader context of space sustainability, check out our piece on The Growing Challenge of Space Debris. To understand the rocket technology that gets these servicers into orbit, explore our guide on Modern Launch Vehicle Innovations.