Have you ever noticed how the world seems solid, predictable, and there when you open your eyes in the morning? Your coffee cup is exactly where you left it, your chair doesn’t dissolve into a cloud of possibilities when you sit down, and the tree outside your window isn’t simultaneously a sapling and an ancient oak. Our everyday experience is one of definite, settled reality.

Now, take a journey to the subatomic world for a moment. Here, things aren’t so settled. An electron isn’t necessarily here or there; it can be in a blend, or a superposition, of many places at once. A particle can act like a wave, spreading out and interfering with itself. This isn’t speculation; it’s the bedrock of quantum mechanics, the most successful and accurate scientific theory ever devised, powering everything from smartphones to MRI machines.

But there’s a catch. A big, philosophical, mind-bending catch. How do we get from that fuzzy, probabilistic, multiple-potential quantum world to the single, definite reality we experience? This is the Measurement Problem, and its proposed solution, wavefunction collapse, is one of the greatest—and most debated—mysteries in all of science. It doesn’t just puzzle physicists; it strikes at the very heart of what we consider real.

Act I: Setting the Stage – The Weird, Wonderful Quantum World

Before we dive into the problem, we need to appreciate the strange rules of the quantum realm. Forget about tiny billiard balls. At this scale, the universe operates on different principles.

Superposition is the star of the show. It’s the idea that a quantum system (like an electron, a photon, or even a small molecule) doesn’t have a single definite property until we measure it. Think of it not as “the particle is in one specific spot, we just don’t know where,” but rather, “the particle’s location is literally smeared out over a range of possibilities, described by a mathematical entity called the wavefunction.” The wavefunction, often denoted by the Greek letter Psi (Ψ), contains all the possible states of the system and their probabilities.

The classic analogy is Schrödinger’s (in)famous cat. The cat in the sealed box, whose fate is tied to a random quantum event (the decay of an atom), is theoretically in a superposition of being both alive and dead until someone opens the box and looks. Of course, this is a thought experiment designed to highlight the absurdity of scaling quantum weirdness to everyday life. But for a single electron, superposition is as real as it gets.

The Double-Slit Experiment: The Heart of the Weirdness

To truly feel the measurement problem, you have to understand the double-slit experiment. It’s been called the most beautiful experiment in physics.

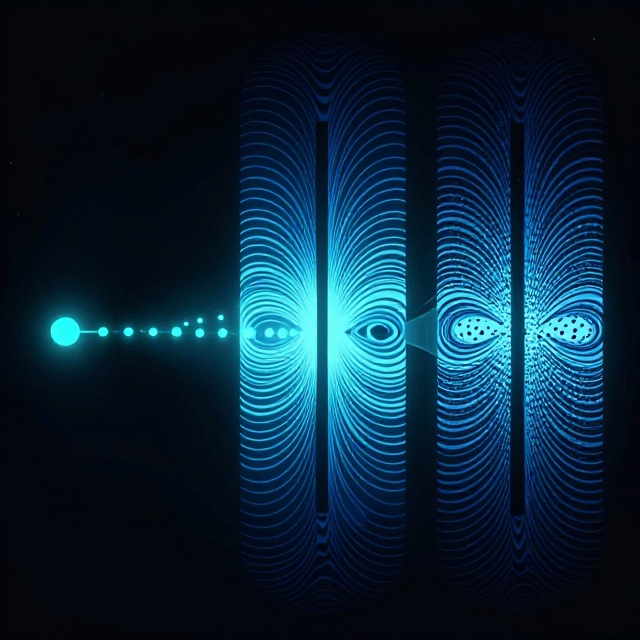

Imagine firing tiny particles, like electrons, one by one at a barrier with two slits. On the other side is a screen that lights up when an electron hits it. If electrons were simple particles, you’d expect two clusters of hits behind the two slits. But that’s not what happens. Instead, you get an interference pattern—a series of light and dark bands. This is the hallmark of wave behavior. It’s as if each electron passes through both slits at once, like a wave, and interferes with itself on the other side. The wavefunction of the electron travels through both slits.

This is baffling enough. But the plot thickens. What if you place a detector at the slits to see which slit each electron actually goes through? The moment you do that, the interference pattern vanishes. You now get the two simple clusters, just as you would for plain old particles. The act of measuring or observing the electron’s path seems to force it to “pick” one slit. Its wavefunction, which was spread out, appears to collapse into a single, definite outcome.

This is the first tantalizing hint of the measurement problem. The rules of quantum mechanics describe a system evolving smoothly and deterministically as a wave—until someone looks. Then, randomness and definiteness take over.

Act II: The Act of Measurement – Where Does the Magic Happen?

So, what is so special about “measurement”? This is the core of the dilemma. In the pristine mathematics of quantum theory, there’s no clear line that separates the “quantum system” from the “classical observer.” The equations just describe the wavefunction evolving. But our experience, and all experimental evidence, tells us that at some point, a single result crystallizes.

The Textbook Story: The Copenhagen Interpretation

For much of the 20th century, the dominant view was the Copenhagen Interpretation, championed by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg. It essentially says: “Don’t ask what’s happening before you look.” It proposes a pragmatic, if philosophically unsatisfying, solution:

- The wavefunction (Ψ) is a complete description of reality.

- It evolves smoothly according to the Schrödinger Equation—until a measurement is made.

- Upon measurement, Ψ collapses probabilistically into one of the possible eigenstates (definite states). The probability of each outcome is given by the square of the wavefunction’s amplitude (the Born Rule).

- The measurement apparatus must be described classically; it is the “cut” between the quantum and classical worlds.

In this view, collapse is a fundamental, irreducible process. It’s a postulate added to the theory by hand to match what we see. But it raises huge questions: What exactly counts as a “measurement”? Is it a conscious human observer? A photographic plate? A cat? Where do you draw the line? The Copenhagen Interpretation is famously silent on the mechanism of collapse—it just happens.

As physicist John Wheeler put it, we seem to live in a “participatory universe,” where observation plays a crucial role in bringing facts into existence. This is a profound shift from the classical idea of a universe that exists independently of us.

Act III: Is Wavefunction Collapse Real? The Quest for Alternatives

The unease with the mysterious, instantaneous “collapse” of the wavefunction has led to several brilliant and mind-bending alternatives. These aren’t wild speculations; they are rigorous, mathematical interpretations of the same quantum equations.

1. The Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI): No Collapse Needed

Proposed by Hugh Everett III in 1957, this is perhaps the most radical and elegant solution. Everett took the Schrödinger Equation utterly seriously: the wavefunction never collapses. It just keeps evolving, deterministically.

So, what happens during our “measurement”? According to MWI, the observer becomes entangled with the quantum system. When you look at Schrödinger’s cat, the universe doesn’t choose between “you see a live cat” and “you see a dead cat.” Instead, the wavefunction branches. In one branch, there is a version of you seeing a live cat and feeling relief. In another, completely separate branch, a version of you sees a dead cat. Both are equally real, but they have decohered—they no longer interact or interfere with each other. Every quantum possibility plays out in a vast, ever-branching multiverse.

There’s no special role for measurement or consciousness. Collapse is an illusion; we only perceive one branch because we are trapped within it. As physicist David Deutsch argues, this interpretation takes reality seriously and removes the “magic” of observation. You can explore this perspective further in Sean Carroll’s deep dive, Something Deeply Hidden: Quantum Worlds and the Emergence of Spacetime.

2. Objective Collapse Theories: Adding a Tiny Kick

These theories, like the GRW (Ghirardi–Rimini–Weber) theory or models involving gravity (like Roger Penrose’s ideas), propose that collapse is a real, physical process, but it’s not triggered by consciousness. Instead, they add a tiny, random modification to the Schrödinger Equation. For a single particle, this “collapse” effect is negligible and incredibly rare. But for a large object (like a cat or a measurement device), which contains trillions of particles, the probability of a collapse becomes effectively certain in a tiny fraction of a second.

In this view, superposition has a finite size or mass limit. Something the size of a cat cannot be in a superposition for any measurable time; it spontaneously and objectively collapses to a definite state. This provides a clear, physical threshold and makes testable predictions that differ from both Copenhagen and Many-Worlds. Experiments are ongoing to test these limits.

3. The DeBroglie-Bohm Pilot-Wave Theory: A Return to Determinism

This is a fascinating outlier. It says that particles are real point-like objects with definite positions at all times. But they are guided by the wavefunction, which acts as a “pilot wave” or a “quantum potential.” The wavefunction still exists and evolves, but it doesn’t collapse. It simply guides the particle along a definite, but hidden, trajectory.

In the double-slit experiment, the electron particle goes through only one slit, but the pilot wave goes through both. The interference pattern arises because the particle’s path is influenced by the whole wave. Measurement is just us discovering the particle’s pre-existing position. This theory is fully deterministic (no fundamental randomness), but it requires accepting “non-local” influences—spooky actions that can travel faster than light to guide the particles. It’s a reminder that our classical intuitions can be salvaged, but at a high price.

Act IV: Why Does This Matter? It’s Not Just Philosophy

You might wonder: if all these interpretations make the same experimental predictions, why should we care? It’s just philosophy, right?

Wrong. This debate drives technology, shapes our understanding of the universe’s fabric, and forces us to confront the limits of knowledge.

- Quantum Computing: A quantum computer relies on manipulating superpositions (qubits). The interpretation debate directly informs how we understand what’s happening during a computation. Is the computer exploring many worlds in parallel (favored by MWI)? Or is it exploiting a single, complex wavefunction that collapses at the end? The practical roadmap may be the same, but our conceptual understanding is vastly different.

- The Nature of Reality: This is the big one. Do we live in a universe where consciousness plays a role in shaping reality (Copenhagen)? A near-infinite multiverse where every possibility is real (MWI)? Or a world with hidden variables (Bohmian)? The answer to the measurement problem is an answer to the most fundamental question we can ask: what is the world?

- The Quest for a Deeper Theory: Many physicists believe quantum mechanics is not the final word. It clashes spectacularly with our other supremely successful theory: Einstein’s General Relativity (which describes gravity). Understanding how and why the quantum world transitions to the classical world—solving the measurement problem—may be the crucial clue we need to find a Theory of Quantum Gravity, a “theory of everything.” As explored in resources like the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s entry on Quantum Mechanics, the foundational issues are still wide open.

The Human in the Loop: Where Do We Stand?

Today, there is no scientific consensus on the “correct” interpretation. Polls of physicists show a shift from the dominance of Copenhagen towards Many-Worlds and other alternatives, but with significant diversity of opinion. The field is vibrantly alive.

The measurement problem holds up a mirror to our own place in the cosmos. For centuries, science painted a picture of humans as passive observers of a clockwork universe. Quantum mechanics, through the puzzle of measurement, suggests we might be integral participants. The act of questioning, of experimenting, of looking, seems inextricably woven into the tapestry of facts.

Perhaps the most honest answer to “What is wavefunction collapse?” is this: We still don’t know. It is an active frontier. It might be a physical process, a branching of worlds, an illusion, or something beyond our current imagination.

But that’s the thrill of it. This great quantum mystery reminds us that reality, at its deepest level, is not a solved puzzle to be filed away. It is a living, breathing question—an invitation to look deeper, think harder, and remain forever amazed at the strange and wonderful universe we find ourselves in. The next time you look at a settled, definite object—your hands, a tree, the moon—remember: beneath that solid surface lies an ocean of possibilities, waiting for us to understand how they become the singular, shared world we call home.

FAQ Section

Q: Does this mean consciousness causes wavefunction collapse?

A: This is a common and intriguing misconception stemming from some early interpretations. Most modern physicists reject the idea that a human mind is necessary. In standard theory, any irreversible interaction that “records” information (like a photon hitting a detector screen) can trigger decoherence or collapse. Consciousness is seen as a byproduct, not a cause, of the physical process.

Q: If it’s just a theory, why is the Measurement Problem a big deal?

A: While the predictions of quantum mechanics are rock-solid, the story about what’s fundamentally happening is incomplete. The problem is that our most accurate theory of reality has a glaring, unexplained gap: the transition from possibility to actuality. It’s like having a perfect map that suddenly says, “and then a miracle happens here.” Scientists seek a complete, coherent picture of nature.

Q: Which interpretation is correct?

A: There is currently no scientific consensus. All major interpretations (Copenhagen, Many-Worlds, Objective Collapse, etc.) make identical predictions for all experiments conducted to date. Choosing between them is currently a matter of philosophical preference, aesthetic taste, and which set of puzzling implications you find more palatable. Future experiments testing the limits of quantum superpositions may one day rule some out.

Q: What’s the difference between “superposition” and “collapse”?

A: Think of superposition as the “before” state. It’s the mathematical description of all possible outcomes and their probabilities—the electron being both here and there. Collapse (or its alternative, branching) is the “after” event. It’s the process by which that spread-out menu of possibilities reduces to the single, definite outcome we actually observe—the electron being here.

Q: Is the Many-Worlds Interpretation just science fiction?

A: No, it is a serious and respected interpretation within theoretical physics. Its appeal is that it removes the arbitrary “collapse” rule by taking the pure Schrödinger equation to its logical conclusion. The cost is an exponentially multiplying multiverse. While it feels extravagant, proponents argue it’s more parsimonious than adding a collapse mechanism we don’t understand. It’s a matter of fierce and legitimate debate.

Q: Does this affect my daily life?

A: Not directly in your routine, but absolutely in the technology you use. The entire field of quantum information science (which includes the quest for quantum computers and ultra-secure communication) relies on expertly manipulating superposition and entanglement. Understanding how these states interact with the environment (the core of the measurement problem) is the key engineering challenge in building these devices.